Duodenum

Duodenum

-

Gross anatomy: The duodenum, jejunum, and ileum make up the small intestine. The duodenum has four parts: the first part (bulb), the second part (descending segment), the third part (horizontal segment), and the fourth part (ascending segment). In the abdominal cavity, it forms a C-shaped loop, with the head of the pancreas sitting in the concavity of the C.

The duodenal bulb is attached to the hepatoduodenal ligament, which connects it to the undersurface of the liver. The hepatoduodenal ligament contains the portal vein, hepatic artery, and common bile duct.

The duodenum continues as the jejunum at the duodenojejunal flexure, which is to the right of the inferior mesenteric vein. The ligament of Treitz (the suspensory ligament of the duodenum) is a fibromuscular, double fold of peritoneum that suspends the duodenojejunal flexure from the retroperitoneum. Clinically, it’s used as a landmark to separate upper from lower GI bleeding: upper GI bleeding is proximal to the ligament, and lower GI bleeding is distal to it. Its position is also used to assess for malrotation of the gut, since a normal position of the ligament rules out malrotation.

The major and minor duodenal papillae are key landmarks in the second part of the duodenum. The major papilla (papilla of Vater) is where the dilated junction of the bile duct and pancreatic duct enters the duodenum. It’s surrounded by the sphincter of Oddi. This sphincter controls the flow of bile and pancreatic juice into the duodenum and prevents reflux of duodenal contents back into the ducts. Obstruction at the sphincter of Oddi can lead to pancreatitis and cholangitis. ERCP is performed via the sphincter of Oddi.

The minor duodenal papilla is located proximal to the major duodenal papilla. It’s an embryologic remnant that represents the opening of the accessory pancreatic duct of Santorini. Except for the first segment, all other segments of the duodenum are secondary retroperitoneal structures.

-

Histology: The duodenum is lined by simple columnar epithelium. It has:

- Numerous finger-like projections of epithelium and lamina propria called villi

- Openings of intestinal glands

- Semilunar folds of mucosa and submucosa called plicae circulares (valves of Kerckring)

These structures increase the absorptive surface area. Enterocytes absorb nutrients. They’re joined by tight junctions and have microvilli (microscopic protrusions of the luminal surface made of cell membrane and cytoplasm). The microvilli are coated by filamentous glycoproteins called the glycocalyx.

The epithelium also contains goblet cells and Brunner’s glands; both secrete mucus. Brunner’s glands are characteristic of the duodenum and also secrete bicarbonate, which helps neutralize gastric acid.

The epithelium invaginates into the lamina propria to form the crypts of Lieberkuhn. The crypts contain several cell types:

i) Stem cells: These have high mitotic activity and replace enterocytes and goblet cells every 3-6 days.

ii) Paneth cells: These immune cells are located at the base of the crypts and secrete lysozyme, TNF alpha, and defensins.

iii) Enteroendocrine cells: There are five types:

- I cells secrete cholecystokinin

- S cells secrete secretin

- K cells secrete gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP)

- L cells secrete glucagon like peptide 1 (GLP 1)

- Mo cells secrete motilin

Peyer’s patches are part of the gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and are found in the mucosa and submucosa. They’re aggregates of lymphoid follicles lined by antigen-transporting M cells.

Jejunum and Ileum

The loops of the jejunum and ileum occupy the center of the abdominal cavity and pelvis. Compared with the jejunum, the ileum has a thinner wall and a smaller lumen.

Histologically, you can distinguish them from the duodenum by the absence of Brunner’s glands. Peyer’s patches are more prominent in the ileum. The jejunum is devoid of Peyer’s patches and Brunner’s glands. The rest of the histologic appearance of the jejunum and ileum is the same as the duodenum.

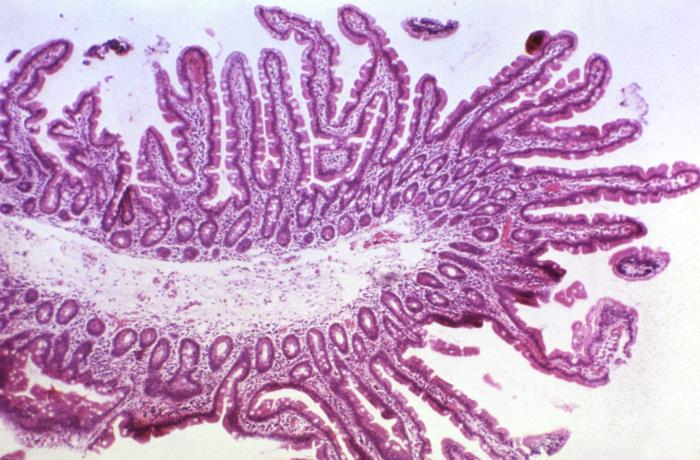

This photomicrograph depicts the cytoarchitecture exhibited by a normal section of intestinal epithelial mucosa. Note the numerous, robust mucosal projections known as villi, as well as the associated intestinal glands, or crypts of Lieberkühn, all in a healthy state. This section was obtained as an intestinal biopsy specimen.

Large intestine

The large intestine consists of the cecum and appendix, colon, rectum, and anal canal. It’s called the large intestine because its lumen is wider than the small intestine, even though the small intestine is longer.

The appendix, transverse colon, and sigmoid colon have a mesentery. The ascending and descending colon, rectum, and anal canal are retroperitoneal. The cecum does not have its own mesocolon, but it shares the ileocolic mesentery.

-

Cecum and appendix: The ileum ends at the cecum at the ileocecal junction, which is guarded by the ileocecal valve. The cecum occupies the right iliac fossa. It’s the widest part of the large intestine and is mobile, which predisposes it to volvulus. It continues as the ascending colon.

The appendix arises from the posteromedial part of the cecum, below the ileocecal junction. You can locate it by tracing the teniae coli. It’s a true diverticulum because it contains all layers of the colon. Although the appendix arises from a constant base, it can lie in several positions, including retrocecal, pelvic, subcecal, pre-ileal, or post-ileal.

Spinal level T10 supplies the appendix, and its dermatome is at the level of the umbilicus. For this reason, appendiceal pain may be felt in the periumbilical area. Recent research has suggested that the appendix should no longer be considered a vestigial organ.

-

Colon: The colon begins at the cecum as the ascending colon on the right side of the abdominal cavity. It continues as the transverse colon, then bends under the spleen to become the descending colon on the left side of the abdominal cavity. It’s followed by the sigmoid colon, which is the narrowest region of the colon.

Histology of the colon: The colon has four layers. From inside to outside, these are mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa, and serosa. The muscularis externa has an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer. The outer longitudinal layer is arranged into three compact bands called teniae coli. The teniae coli converge at the base of the appendix.

Contraction of the teniae coli produces colonic haustrations, an important radiologic feature used to identify the colon. The outer surface of the serosa has outpouchings of peritoneum filled with fat called appendices epiploicae.

The luminal surface of the colon shows numerous openings of colonic glands. Rugae, villi, and plicae circulares are absent. The epithelium contains enterocytes and mucus-producing goblet cells. GALT can be present in the lamina propria.

Enterocytes, goblet cells, Paneth cells, endocrine cells, and stem cells are located in the crypts of Lieberkuhn. Stem cells regenerate the epithelium, with about 10 billion cells replaced each day in the colon alone. Gli1-positive cells, located adjacent to the stem cells, secrete activator proteins called Wnt proteins. These are important in everyday regeneration and repair of the epithelium and in the pathogenesis of colon cancer.

-

Rectum: The rectum begins at the level of the S3 vertebra and continues as the anal canal. The transition from rectum to anal canal occurs at the level of the levator ani muscle. Puborectalis (a component of the levator ani) forms a sling at the anorectal junction. When puborectalis relaxes, it straightens the rectum to facilitate defecation; when it contracts, it angulates the rectum to prevent defecation.

Houston’s valves of the rectum are transverse submucosal folds composed of circular muscle, usually three or four in number. Taeniae coli are absent in the rectum.

In males, the prostate and rectovesical pouch are anterior to the rectum. In females, the rectouterine pouch (pouch of Douglas) is anterior to the rectum. Waldeyer’s fascia is posterior to the rectum.

Histologically, the rectum is similar to the rest of the large intestine: it’s lined by simple columnar epithelium and is rich in goblet cells.

-

Anal canal: The anal canal has distinct anatomy because it has two separate embryologic origins. It’s divided into an upper two-thirds and a lower one-third by the pectinate (dentate) line.

The upper part has longitudinal mucosal columns called columns of Morgagni (anal columns), which lie at the pectinate line. At the base of these columns are transverse mucosal folds that form the anal valves. The anal valves demarcate the anal sinuses, which receive the openings of the anal glands.

The upper anal canal is lined by simple columnar epithelium with many mucus-secreting goblet cells. About 1-2 cm above the pectinate line is a transitional zone with cuboidal epithelium, where the mucosa gradually transitions from simple columnar to stratified squamous epithelium.

The lower anal canal is lined by nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The junction of the anal canal with the perianal skin is the anal verge, which is lined by keratinized stratified squamous epithelium.

Above the pectinate line, innervation is via the autonomic inferior hypogastric plexus. Below the pectinate line, innervation is via the somatic inferior rectal branch of the pudendal nerve.

Blood supply of the gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract is supplied mainly by the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA).

- The celiac trunk supplies foregut structures: the stomach and up to the second part of the duodenum.

- The SMA supplies the distal part of the duodenum, the rest of the small intestine, and the proximal colon up to the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon.

- The IMA supplies the distal colon, starting from the distal one-third of the transverse colon to the upper part of the rectum.

There are extensive anastomoses between the arteries supplying the gastrointestinal tract. This forms arterial arcades along the mesenteric border of the stomach, small intestine, and colon.

Quick note: The mesenteric border is where the mesentery attaches to the intestinal wall. The antimesenteric border is the opposite side.

Perpendicularly oriented arteries called vasa recta emerge from these arcades and penetrate the walls of the hollow viscera they supply, ultimately forming a plexus within the submucosa.

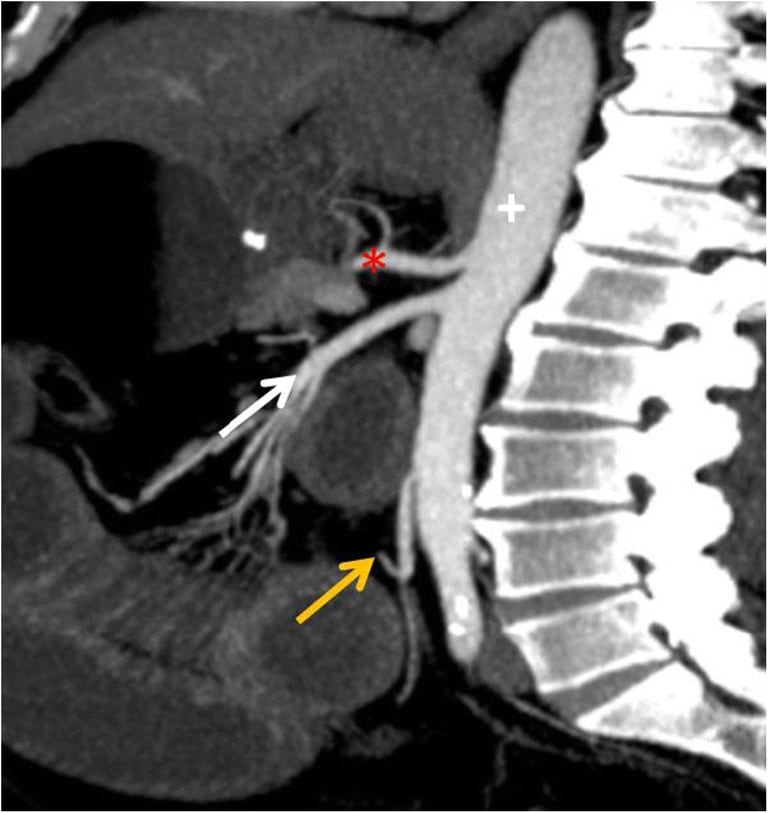

Anatomy. Sagittal CT MIP (maximum intensity projection) image shows three major arteries that supply the bowel, coeliac trunk (asterisk), superior mesenteric artery (white arrow) and inferior mesenteric artery (orange arrow), which are visceral branches of the abdominal aorta (+)

-

Celiac trunk: The celiac trunk is the first major branch of the abdominal aorta, arising at the level of the T12 vertebra. It gives off three branches: the left gastric, common hepatic, and splenic arteries. Together, the celiac trunk and its branches supply the stomach, lower esophagus, up to the second part of the duodenum, spleen, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas.

-

Superior mesenteric artery: The SMA is a branch of the abdominal aorta arising at the level of the L1 vertebra. It gives rise to the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, jejunal and ileal branches, and the ileocolic, right colic, and middle colic arteries.

-

Inferior mesenteric artery: The IMA arises from the abdominal aorta at the level of the L3 vertebra. It gives rise to the left colic artery, sigmoid arteries, and superior rectal artery.

-

Marginal artery of the colon or artery of Drummond: This artery is formed by anastomoses between SMA and IMA branches via the colic and sigmoid arteries. It runs close to the colon.

-

Arterial supply of the stomach: The stomach is supplied mainly by five arteries. The left gastric artery (a branch of the celiac trunk) and the right gastric artery (a branch of the common hepatic artery) anastomose near the lesser curvature. The left gastroepiploic artery (a branch of the splenic artery) and the right gastroepiploic artery (a branch of the gastroduodenal artery) anastomose near the greater curvature.

The gastroduodenal artery is a branch of the common hepatic artery. It lies close to the posterior wall of the first part of the duodenum and can be eroded by a duodenal ulcer, causing life-threatening hemorrhage.

Short gastric arteries branch from the splenic artery and supply the fundus.