Ischemic colitis: Colonic inflammation caused by decreased blood supply to the bowel wall. The reduced perfusion may be:

Ischemia may be transient, but in severe, persistent cases it can progress to gangrene of the colon.

Risk factors include age >65 years, female gender, smoking, HT, DM, COPD, IHD, peripheral vascular disease, IBS, sickle cell disease, constipation, abdominal surgery, thrombophilia, etc.

Symptoms are often precipitated after a colonoscopy, enema, laxative use, heavy drinking, pancreatitis, shock, and burns.

It presents with acute abdominal pain, cramping, hematochezia, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension. Peritoneal signs (rebound tenderness, guarding, rigidity), along with fever, tachycardia, and leukocytosis, suggest severe disease with transmural necrosis and perforation.

Small vessel disease is more commonly associated with ischemic colitis than large vessel disease. Initially, ischemic changes involve the mucosa and submucosa, and may eventually extend deeper, causing full-thickness gangrene in severe cases. Changes are more prominent along the antimesenteric border of the colon. Revascularization is sometimes associated with reperfusion injury to the colon.

A high index of clinical suspicion is needed because ischemic colitis can have vague, transient features and often clinically mimics other inflammatory disorders.

Imaging studies may show:

CT with contrast is the imaging modality of choice. Danger signs on imaging are pneumoperitoneum, pneumatosis intestinalis, and pneumatosis coli (air in the mesenteric or portal vein).

Colonoscopy is the gold standard for confirming the diagnosis. Findings include pale, edematous mucosa with ulcerations, hemorrhages, and sometimes pseudomembrane formation. Gangrenous bowel appears grayish-black and immobile.

Management depends on severity. Most cases are treated with supportive therapy, bowel rest, parenteral nutrition, nasogastric tube, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Deteriorating cases require bowel resection surgery.

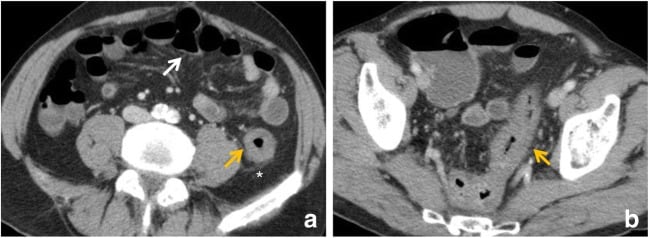

Ischaemic colitis in a 74-year-old male with vasculitis who presented with abdominal pain and bloody diarrhoea. (a, b) Contrast-enhanced CT scan reveals involvement of the sigmoid colon and splenic flexure (orange arrows) with marked wall thickening and pericolic streakiness (asterisk). Diagnosis was confirmed at colonoscopy and biopsy. The ischaemic process resolved

Paralytic or adynamic ileus: A motility disorder caused by failure of peristalsis, typically affecting all segments of the gastrointestinal tract, including the small and large intestines.

It can result from surgery (especially abdominal surgery), electrolyte imbalances (e.g., hypomagnesemia), acid-base disturbances, uremia, pancreatitis, vitamin deficiencies, hypothyroidism, trauma, DM, drugs (e.g., narcotics, anesthesia), mesenteric ischemia, intraperitoneal infection, etc.

It presents with abdominal distension, absent bowel sounds, nausea, and vomiting. Pain is not prominent, unlike in true bowel obstruction.

Preferred investigations include abdominal CT scan with Gastrografin, barium enema, and abdominal X ray. Imaging shows dilated loops of small and large intestine with air-fluid levels. Some cases may have local paralytic ileus.

Treatment is supportive and includes bowel rest, nasogastric tube decompression, and correction of underlying disorders (e.g., acid-base imbalances). Early enteral feeding may help, as well as drugs like neostigmine, erythromycin, metoclopramide, and lactulose. Spontaneous return of gastrointestinal motility is typically seen in 2-4 days.

Diverticulosis and diverticulitis of the colon: Diverticulosis is a common disorder of old age characterized by the formation of multiple sac-like outpouchings (diverticula). Diverticulitis occurs when diverticula become inflamed and is potentially lethal.

Diverticula form at weak points in the colon wall, specifically where the vasa recta penetrate the colon wall. They are composed of herniating mucosa and submucosa. Abnormal elastin deposition and increased collagen cross-linking are seen in the colonic wall in patients with diverticulosis. Increased intraluminal pressure in the colon, potentiated by constipation and lack of fibre in the diet, predisposes to diverticula formation. It is more common in the left colon.

Most patients with diverticulosis are asymptomatic. Some may present with mild abdominal pain, alterations in bowel habits, and blood in stools. Diagnosis is confirmed by colonoscopy, which shows diverticula.

Treatment includes increasing fibre in the diet, probiotics, being more active, and supportive therapy for bleeding. Mesalazine and rifaximin may reduce symptoms. Surgery is needed if massive bleeding occurs or if problematic symptoms with increased risk of infection are present.

Diverticulitis results from micro- or macro-perforations in diverticula, which may be caused by food particles or obstruction by fecaliths with resultant inflammation. It may be complicated by abscess formation, fistula, peritonitis, and sepsis. Smoking and NSAIDS increase the risk of perforation in diverticulitis.

Patients present with fever, abdominal pain (typically in the left lower quadrant), tenderness, diarrhea or constipation, nausea, vomiting, and leukocytosis. Colovesicular fistula may present with passing gas and feces in urine. Peritoneal signs may be present.

Endoscopy is contraindicated because the inflamed bowel is prone to perforation. CT scan with contrast is the investigation of choice. Imaging shows thickening of the bowel wall, pericolic fluid, pericolic fat stranding, and may show complications such as fistula or abscess.

Treatment includes bowel rest, intravenous fluids, and broad-spectrum antibiotics with anaerobic coverage (metronidazole or clindamycin). Surgery is needed for complications and in severe inflammation; bowel resection with colostomy and anastomosis is done when appropriate.

Sign up for free to take 2 quiz questions on this topic