Mesenteric ischemia is rare but potentially fatal, so early diagnosis requires a high degree of clinical suspicion. It’s typically seen in people older than 60 years, especially with conditions that predispose to ischemia such as HT, DM, atrial fibrillation, dyslipidemias, smoking, arterial dissection, cocaine abuse, etc.

Patients usually present with severe abdominal pain along with nausea, vomiting, and bloody diarrhea. Some report post-prandial abdominal pain (abdominal angina). Depending on the cause, the presentation may be acute or chronic.

A key clinical clue is that the abdominal pain is out of proportion to the physical exam. Early on, peritoneal signs may be absent. As ischemia progresses, you may see abdominal distension, guarding, rebound, rigidity, and absent bowel sounds. Fever and shock can occur once sepsis develops.

Common causes are mesenteric artery embolism, mesenteric artery thrombosis, mesenteric vein thrombosis and non-occlusive ischemia.

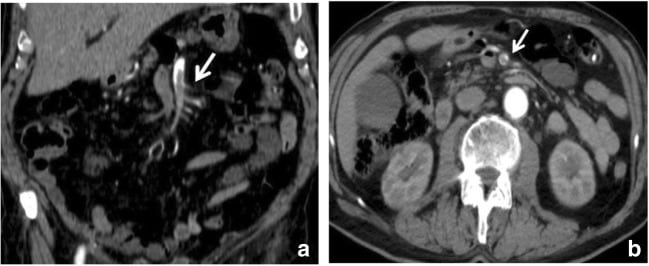

Arterial occlusion. Contrast-enhanced CT image of the abdomen in a 54-year-old female with superior mesenteric arterial thrombosis. a, b: Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan demonstrates a thrombus in the superior mesenteric artery in coronal (a) and axial plane (b) (white arrow)

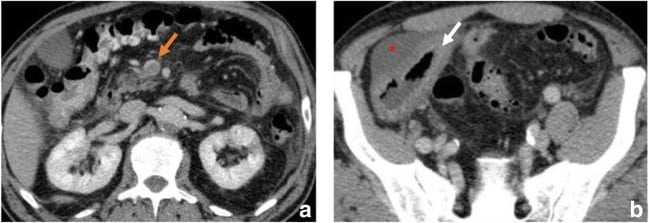

Venous occlusion. Contrast-enhanced CT image of the abdomen in 49-year-old female with superior mesenteric vein thrombosis. (a) Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan shows a thrombus in the superior mesenteric vein in axial plane (orange arrow); (b) wall thickening of the ascending colon (white arrow). Ascites (*) is also visible

Local findings include areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, ulcerations and infarcts. Early in the disease, superficial necrosis is seen in the mucosa, followed by damage to the submucosa and muscularis propria. Continued ischemia can progress to full-thickness infarction.

Mucosal damage allows bacterial invasion from the bowel lumen into the bloodstream, leading to septicaemia and sepsis.

Abdominal X rays are normal early in the disease. In later stages, imaging may show distended bowel loops, thickening of the bowel walls, and air in the bowel wall (pneumatosis intestinalis), which indicates septicaemia and invasion of microbes from the bowel lumen into the wall. Bowel wall edema can produce a “halo sign” or “target sign” on CT scan. Mesenteric fat-stranding may also be seen.

Preferred investigations are CT angiography (CTA) and conventional mesenteric angiography. Conventional angiography also allows local delivery of thrombolytics and papaverine to lyse the thrombus or embolus. An advantage of CTA is that it’s more readily available and can help rule out other diagnoses. MRA can be used as a substitute.

Treatment is supportive with fluid resuscitation, antibiotics like ceftriaxone and metronidazole, and anticoagulants like heparin, warfarin, antiplatelet therapy, and revascularization with embolectomy, angioplasty, and surgical intervention with resection of gangrenous bowel. Emergency laparotomy should be done in the presence of peritoneal signs.

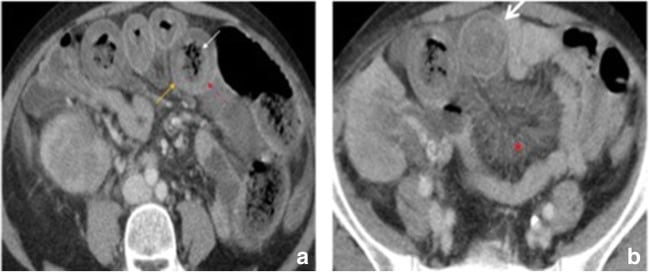

Bowel wall thickness and enhancement. a Contrast-enhanced axial CT images show a target sign (larger white arrow) in the small bowel wall due to mesenteric venous occlusion. b The vascular engorgement (*) and oedema of the bowel wall in turn lead to leakage of extravascular fluid into the bowel wall and mesentery. The resultant oedematous bowel may have a “halo” or “target” appearance due to mild mucosal enhancement (straight white arrow), submucosal and muscularis propria nonenhancement (red arrow), and mild serosal/subserosal enhancement (orange arrow). Bowel wall thickness is greatly increased measuring up to 1.5 cm

Whipple disease or non-tropical sprue or intestinal lipodystrophy: It is a chronic, multisystem, malabsorption disorder caused by intestinal infection with the bacteria Tropheryma whipplei. It is seen more commonly in individuals who are HLA B27+. It presents with diarrhea, steatorrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, joint pain, fatigue, darkening of skin and neurological symptoms such as ataxia, memory loss, confusion, seizures and visual disturbances. Biopsy shows PAS positive macrophages with Gram-positive and non-acid fast bacilli. Treatment is with penicillin G, ceftriaxone, or prolonged administration of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Vitamin and iron supplementation may be needed.

Short bowel syndrome: It is a malabsorptive syndrome that follows resection or functional loss of part of the small bowel. It is seen after surgical resection of the small bowel, mesenteric ischemia, Crohn’s disease, malignancies, etc. It presents with diarrhea, dehydration, weight loss, anorexia, fatigue, steatorrhea, and nutritional deficiencies. Treatment is with total parenteral nutrition, eating small but frequent meals, octreotide, and supportive therapy.

Lactose intolerance: It is caused by acquired or genetic deficiency of the small intestinal brush border enzyme lactase. Lactase breaks down lactose to glucose and galactose. Lactase deficiency may be secondary to IBD, abdominal surgery, gastrointestinal infections, etc. Undigested lactose in the gut increases the osmotic load, causing an osmotic diarrhea. Fermentation of lactose by gut microbes releases gases like hydrogen, carbon dioxide, methane, and short chain fatty acids. Clinical features include bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and excessive gas after consumption of lactose containing foods like milk and milk products. Some patients may have fatigue, arthralgia, and mouth ulcers. Diagnosis is by clinical history, hydrogen breath test (increase in breath hydrogen after lactose consumption), and determining lactase activity from small intestinal biopsy. Treatment is by avoiding lactose in the diet, using probiotics, and enzyme replacement.

Blind loop syndrome or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO): It results from bacterial overgrowth in a segment of the small intestine that is not in continuity with the rest of the bowel and forms a “blind loop.” This can occur after surgeries like gastric bypass, or due to intestinal adhesions, intestinal diverticulosis, Crohn’s disease, scleroderma, radiation enteritis, celiac disease, and other conditions like DM that slow the movement of bowel contents. SIBO interferes with absorption and digestion of food and leads to deficiency of vitamins A, D, E, K, and B12 with resulting disorders, osteoporosis from decreased calcium absorption, and renal stones. Temporary lactose intolerance may occur. SIBO presents with bloating, flatulence, abdominal pain, fatigue, weight loss, diarrhea, and constipation. Diagnosis can be confirmed by a breath test or gas chromatography after ingestion of glucose or lactulose, showing an increase in hydrogen and methane. Endoscopic aspiration of small intestinal fluid followed by bacterial cultures and colony counts can help quantify the bacterial overgrowth. Treatment is with oral antibiotics such as rifaximin and/or neomycin, vitamin supplementation, and surgical correction.

Bowel obstruction presents with abdominal pain that is initially colicky and later becomes continuous, along with abdominal distension, nausea, and vomiting. Vomiting is bilious if the obstruction is below the opening of the bile duct and non-bilious if the obstruction is above it. Other features include failure to pass flatus and bowel movements (obstipation), peritoneal signs, and fever and shock in bowel perforations.

On abdominal exam, you may find tympanic percussion and high-pitched borborygmi early in obstruction, followed by minimal or absent bowel sounds as obstruction progresses.

Imaging studies including plain X rays and CT scan with contrast are used for diagnosis. Ultrasound and MRI can be used if radiation exposure must be avoided, such as in pregnant women and children. A perforated viscus can be seen as air under the diaphragm on erect or left lateral decubitus films.

Conservative management with NPO (nothing per oral), decompression with naso-gastric suction or a long intestinal tube, and intravenous fluids is used when there is no evidence of ischemia or perforation.

Water-soluble or gastrografin contrast orally can help in two ways:

The underlying condition causing the obstruction should be treated, such as repairing a hernia or relieving obstruction from a malignant growth by stenting or surgery.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO)

Causes: Adhesions (most common), hernias, malignancies, IBD, radiation, gallstone ileus, foreign bodies, bezoars, intussusception, endometriosis

Findings on imaging studies: Dilated small bowel loops; dilated loops more centrally located; absence of air in the colon; valvulae conniventes seen; air-fluid levels

Large bowel obstruction (SBO)

Causes: Colon cancer (most common), volvulus, diverticula, IBD, postanatomotic stenosis, ischemic stenosis

Findings on imaging studies: Dilated loops of colon; dilated loops located peripherally; cecum may be distended; Dilated haustra; air-fluid levels

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is an inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract that can cause necrosis, bacterial invasion, and sepsis. It is seen in premature infants, typically 8-10 days after birth.

Breastfeeding is protective. Factors associated with increased risk include antibiotic use, IUGR or very low birth weight, enteral feeding, umbilical catheterization, maternal gestational diabetes, etc.

Immaturity of the intestinal mucosa and hyper-reactive local immune responses are implicated in the pathogenesis of NEC. These include increased expression of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), increased transcription of NF-kB, a cytokine cascade with increased IL8 levels, and reduced biodiversity of intestinal microbial flora.

Clinical features include temperature instability, abdominal distension and tenderness, vomiting, bloody stools, discoloration of abdominal wall, lethargy, apnea, bradycardia, and hypotension.

Imaging studies show dilated bowel loops, free air in the abdomen (perforation), portal venous gas, and pneumatosis intestinalis (air in the bowel wall). Treatment is with bowel rest, decompression, antibiotics, and supportive therapy.

Contrast-enhanced CT image of the abdomen in an 82-year-old male with embolism of the superior mesenteric artery. (a) Contrast-enhanced axial CT shows pronounced intrahepatic portal venous gas (branching hypoattenuating areas) extending into the periphery of the left liver lobe (red arrow). (b) Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan shows dilated and gas-filled loops with an extreme thinning of the bowel wall, a “paper thin wall”, due to transmural small-bowel infarction (orange arrow). Pneumatosis (white arrow) is also seen; fat stranding (*) and gas in mesenteric veins (white arrowhead)