Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): IBD is a multifactorial condition characterized by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. It includes two syndromes: Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).

IBD tends to run in families. It’s more common in whites and Ashkenazi Jews. Smoking predisposes to CD, while it has an apparent protective effect in UC. HLA A2 and B27 are associated with CD, while HLA-Bw35, B5, and B27 are associated with UC.

Mutations in NOD2 (a gene involved in innate immunity) carry a high risk of developing CD. NOD2 recognizes components of the bacterial cell wall and triggers an NF-κB response. It also helps mediate the release of defensins.

IBD is caused by an abnormal, exaggerated inflammatory response in a genetically susceptible individual. Inflammatory cells (neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, and mast cells) are recruited into the gastrointestinal tract and release mediators such as cytokines and monokines, free radicals, TGF beta, and leukotrienes. There is also an enhanced CD8+ cytotoxic response and a decreased suppressor T cell response, which together sustain chronic inflammation. The trigger for this immune response is not definitively known.

| Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis |

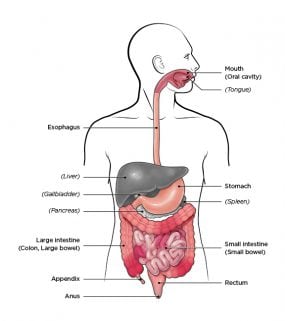

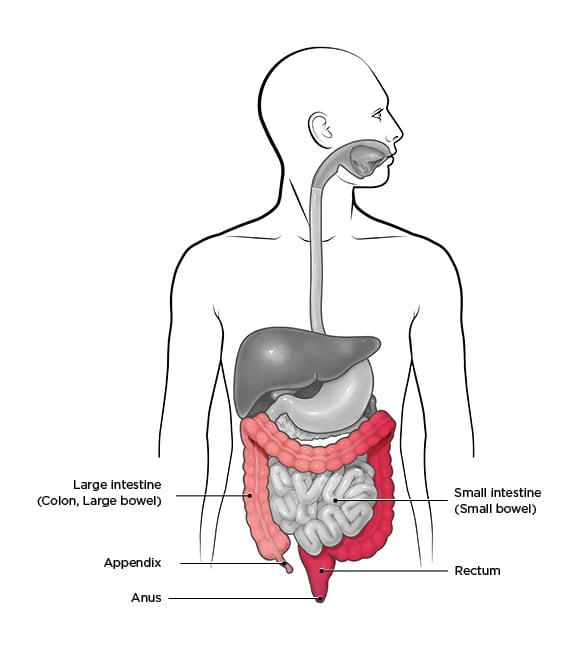

| Can affect any part of the GIT, from mouth to anus. Most commonly involves ileum and colon | Affects the rectum and colon |

| Patchy areas of disease but affects entire wall thickness (transmural), interspersed with healthy areas | Affects areas superficially (mucosa and submucosa) but continuously, starting from the rectum and spreading to involve adjoining colon. |

| Biopsy shows ulceration extending deep to the submucosa; non-caseating granulomas, crypt abscesses (look for neutrophil collections), submucosal edema, neuronal hyperplasia, thickened and fibrosed bowel wall. pseudopolyps are less common | Biopsy shows diffuse mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria, pseudopolyps (composed of granulation tissue, inflamed regenerating mucosa and multinucleated giant cells), crypt abscesses, plasma cells; absence of granulomas, neuronal hyperplasia, submucosal edema or thickened bowel |

| Strictures, fistulas and sinuses may form | No strictures, fistulas or sinuses |

| Skip lesions and serpentine ulcers seen | Continuous involvement hence no skip lesions; superficial, not serpentine ulceration |

| Cobblestone appearance due to healthy mucosa interspersed between depressed, ulcerated areas | Absence of cobblestone appearance of mucosa |

| Mesenteric fat wrapping seen | Absence of fat wrapping |

| Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies or ASCA+ | Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies or ASCA mostly absent |

| p ANCA typically negative | p ANCA + |

Clinical features include persistent diarrhea, abdominal pain and cramping, blood in stools or rectal bleeding, weight loss, and fatigue. The clinical course is typically marked by flare-ups and remissions.

Complications include perforation (UC and CD), toxic megacolon (UC), iliac vein thrombosis, colon cancer, lymphoma, and appendicitis (UC). Vitamin B12 deficiency may occur in CD.

Extraintestinal manifestations are common and include migratory polyarthritis, sacroiliitis, ankylosing spondylitis, pyoderma gangrenosum, clubbing of fingertips, primary sclerosing cholangitis (more in UC), pericholangitis, oxalate stones (CD), uveitis, and cholangiocarcinoma (rare).

Diagnosis is based on clinical features plus endoscopy and imaging such as CT (with oral and/or intravenous contrast; avoid oral contrast in suspected perforations) and MRI.

Findings in CD include wall thickening >3 mm, mucosal hyperenhancement, the “target sign,” engorged vasa recta (the “comb sign”), fistulas, abscesses, and creeping fat stranding in chronic CD.

Endoscopy is preferred over CT/MRI in UC except when toxic megacolon or perforation is suspected; in those settings, CT is preferred. CT findings in UC include thinning of the colonic wall, luminal distension, and pneumatosis. Free intraperitoneal gas is seen with perforation. MRI is preferred in personal disease.

Treatment includes corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone), aminosalicylates (e.g., mesalamine, 5-ASA, or sulfasalazine; helps maintain remission in UC), metronidazole, and immunosuppression with azathioprine or mercaptopurine (for severe or steroid-resistant IBD). Methotrexate can reduce inflammation. Biologics (monoclonal antibodies) include infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept. Additional management includes nutritional supplementation and supportive therapy (e.g., loperamide for diarrhea, bismuth enemas in UC) and colectomy.

Paradoxically, patients treated for autoimmune diseases with anti-TNFα agents (especially etanercept) have an increased risk of developing IBD.

Patients with IBD are at increased risk of colon cancer and should be monitored with colonoscopy after 8-10 years of disease. Colonoscopy in IBD is typically performed every 1-2 years. Flat or polypoid dysplastic lesions may be seen and should be biopsied.

Ogilvie syndrome or acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: This is a non-mechanical pseudo-obstruction caused by loss of colonic motor activity, leading to colonic distension. It occurs in the setting of critical illness (e.g., AMI, sepsis, CCF, pneumonia, trauma) or after surgeries (e.g., total hip replacement, cardiac surgery, abdominal surgery). Severe electrolyte imbalances and medications such as anticholinergics, steroids, and opioids can precipitate Ogilvie syndrome.

It presents with massive abdominal distension and pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, and leukocytosis. Perforation may occur and is most commonly seen in the cecum. Imaging shows a massively dilated colon, especially the cecum and right colon. A water-soluble contrast enema can help with diagnosis and may also decompress the colon. Treatment is mainly supportive; neostigmine, colonic decompression, and cecostomy may help.

Volvulus: Volvulus is abnormal rotation (twisting) of the colon along its mesentery. It is most often seen in the sigmoid colon and cecum. It is dangerous because it can cause a closed-loop obstruction with impaired venous return, bowel ischemia, and perforation with peritonitis.

Risk factors include long mesentery, malrotation, pregnancy, adhesions, neuroleptic drugs, Chagas disease, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, high-fibre diet, chronic constipation, and Hirschsprung disease.

Volvulus presents with abdominal distension, vomiting, pain, fever, constipation, and obstipation (failure to pass flatus). Cecal volvulus presents as a small-bowel obstruction. Less commonly, volvulus may involve the stomach or small intestines (associated with malrotation in children).

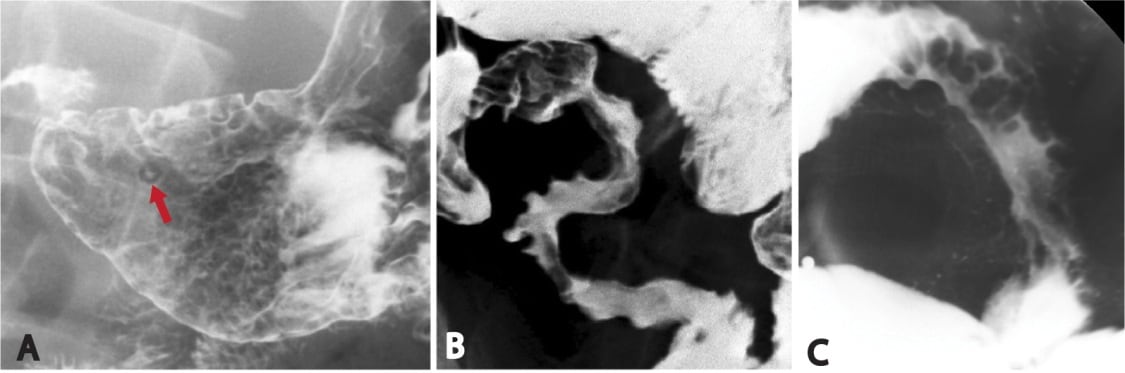

Imaging shows the classic “bent inner tube” or “coffee bean” sign. The cecum may be seen in abnormal locations, such as the upper abdominal quadrants. A barium enema shows the “bird’s beak” sign.

In sigmoid volvulus, sigmoidoscopy is used as a diagnostic and therapeutic measure because it can decompress the colon and may resolve the volvulus. A rectal tube can be passed to aid decompression. In complicated cases, surgical intervention is required in the form of resection (preferred) or sigmoidopexy. The Hartmann procedure is done for bowel perforations.

In cecal volvulus, cecopexy or cecal resection/right hemicolectomy with ileostomy or colostomy is performed. Endoscopy is not done for cecal volvulus because there is no therapeutic benefit.

Hematochezia: Hematochezia is the passage of fresh blood per anus, usually in or with stools. The source is typically the rectum or colon. Rarely, massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding may present as hematochezia.

In elderly patients, diverticulosis and AV malformations (angiodysplasias) are the most common causes. Other causes include hemorrhoids, anal fissure, colon cancer, ischemic colitis, and IBD. Typically, colonic bleeding is mixed with stool, whereas rectal bleeding may coat the stool or appear on toilet paper.

In infants, hematochezia is caused by necrotizing enterocolitis and midgut volvulus. In older children, Meckel’s diverticulum, intussusception, IBD, and juvenile polyps commonly cause hematochezia. It may also be seen in infections such as Campylobacter, shigellosis, and amoebiasis.

Sign up for free to take 5 quiz questions on this topic