Pathophysiology

On gross examination, a cerebral infarct may be pale or hemorrhagic. The affected area is soft and swollen, and there is loss of demarcation between the grey and white matter. Necrotic cells in the infarcted zone undergo liquefactive necrosis.

Pale infarcts are seen in arterial thrombosis. A hemorrhagic infarct looks like a hematoma and usually results from venous thrombosis or breakdown of occlusive arterial emboli.

The earliest light microscopic features of ischemic damage appear a few hours after infarction. If a patient develops irreversible cerebral necrosis and dies within 1 to 2 hours, there may be no visible neuropathological abnormality (by light microscopy) in the affected brain tissue.

The first microscopic sign is deeply eosinophilic, shrunken neurons (“red neurons”) with a darkly basophilic nucleus and clumped chromatin, followed by swollen astrocytes. Loss of cytoplasmic basophilia is due to loss of Nissl substance (rough endoplasmic reticulum). This progresses to outright necrosis. You may see cytoplasmic vacuolation and “ghost neurons” that lack affinity for hematoxylin.

Neutrophils predominate in the first 48 hours, followed by foamy macrophages. Cavitation may be observed by 7-14 days. Macrophages may persist in the infarcted zone for years. Hemorrhagic infarcts may also show hemosiderin-laden macrophages. After 3-4 months, an old cystic cavity forms with peripheral gliosis. Lacunar infarcts appear as small cavitations.

Apart from the typical changes seen in infarcted cerebral tissue, HIE characteristically shows band-like laminar (pseudolaminar) necrosis due to differential sensitivity of neurons to ischemia. The cerebral cortex and striatum are more sensitive than the thalamus and brainstem. The loss of the pyramidal cell layer is more severe than the granular cell layer.

Bilateral hippocampal neuronal loss and gliosis (hippocampal sclerosis) is seen in some cases and presents with memory loss, as in Korsakoff’s syndrome. Myelin damage and vacuolization can give a spongy appearance on cut sections and is seen commonly in carbon monoxide poisoning.

Penumbra is the zone of viable cells surrounding the infarcted zone. Cells in the penumbra show metabolic defects, but they can be saved with prompt revascularization.

(II) ICH or intracerebral hemorrhage: Spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage occurs mostly in patients with hypertension. Aneurysms called Charcot-Bouchard aneurysms form in the branches of the lenticulostriate branches of the cerebral arteries. Rupture of these aneurysms causes ICH.

The common sites of hypertensive intracerebral haemorrhage are the basal ganglia (particularly the putamen and the internal capsule), thalamus, pons, and the cerebellar cortex. Clinically, onset is usually sudden, with headache and loss of consciousness. Signs and symptoms depend on the location of the lesion.

On gross appearance, a haematoma is seen with sharply demarcated borders. It may push adjoining structures and extend into the ventricles. Over time, RBCs in the haematoma undergo lysis, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages can be seen. Resolution of the haematoma takes a few weeks to months, with formation of a cystic lesion surrounded by fibrillary astrocytosis.

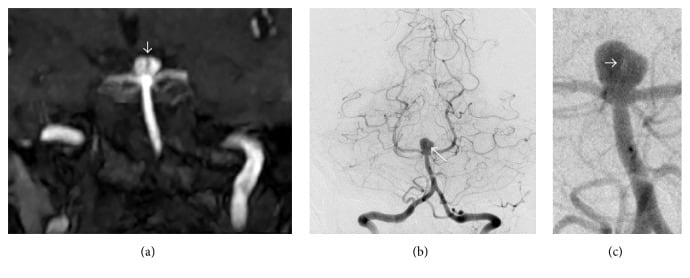

(III) SAH or subarachnoid hemorrhage: This is hemorrhage into the subarachnoid space. It is caused by rupture of congenital or acquired berry aneurysms or bleeding from vascular malformations.

Berry aneurysms are typically seen in young adults, but they can also develop at older ages in the setting of chronic disease. They are saccular aneurysms that develop over time as a result of normal hemodynamic stresses acting on a congenitally defective tunica media. They are frequently associated with polycystic kidney disease and coarctation of aorta.

Common sites are bifurcations of arteries in the circle of Willis:

- Most common: junction of ACA with the anterior communicating artery

- Next: junction of ICA with posterior communicating artery

- Also: bifurcation of MCA

- Also: bifurcation of ICA into the MCA and ACA

Clinically, berry aneurysms are often asymptomatic. A prodrome of headache may precede impending rupture. Rupture of a berry aneurysm with SAH presents with acute onset of severe headache, described as the “worst headache of my life” or a thunderclap headache. Nuchal rigidity, loss of consciousness, and neurological deficits may occur. Rebleeding is common.

CSF examination shows the presence of blood or xanthochromia (yellow CSF), which can be determined visually or by spectrophotometry. RBCs will be present in CSF, but this must be differentiated from a traumatic tap.

In SAH, the amount of RBCs in CSF stays constant, while it gradually decreases in a traumatic tap (from tube to tube). Bilirubin and oxyhemoglobin in CSF will be high. Siderophages (macrophages with engulfed RBCs) are seen in later stages. CT scan shows white densities filling the normally black subarachnoid space, ventricles, cisterns, and/or sulci.

Fusiform aneurysms are vascular dilatations due to atherosclerosis. They are seen most commonly in the basilar artery and are associated with thrombosis and brainstem infarction, and less frequently with rupture and subarachnoid hemorrhage.