We’ll focus on call spreads in this chapter. As a reminder, a call spread is:

Long call & short call

Most math-based spread questions focus on vertical (price) spreads, where both contracts have the same expiration but different strike prices. For example:

Long 1 ABC Jan 60 call

Short 1 ABC Jan 70 call

You’ll use a four-step system to answer maximum gain, maximum loss, and breakeven questions. This system applies to spreads, so the first job is always to correctly identify the strategy.

Let’s work through the spread system using this example:

Long 1 ABC Jan 60 call @ $8

Short 1 ABC Jan 70 call @ $4

Step 1: Net the premiums

The investor pays $8 for the long call and receives $4 for the short call. That creates a net debit (purchase) of $4, or $400 total ($4 × 100 shares).

This step tells you whether the spread’s maximum outcome is a gain or a loss:

Because this spread has a net debit of $400, the maximum loss is $400.

Step 2: Net the strike prices

This step doesn’t give a final answer by itself, but you’ll use it in steps 3 and 4.

Long 1 ABC Jan 60 call @ $8

Short 1 ABC Jan 70 call @ $4

The difference between the strike prices ($60 and $70) is $10.

Step 3: Net strikes - net premium

Take the strike difference ($10) and subtract the original net premium ($4):

$10 − $4 = $6

That $6 is the “other max.” Since step 1 gave us the maximum loss, step 3 gives us the maximum gain:

$6 × 100 = $600 maximum gain

If step 1 gives the maximum loss, step 3 gives the maximum gain. If step 1 gives the maximum gain, step 3 gives the maximum loss.

Step 4: Strike price +/- net premium

Now go back to the original net premium from step 1 (here, a $4 debit) to find breakeven. Use the rule that matches the spread type:

Long 1 ABC Jan 60 call @ $8

Short 1 ABC Jan 70 call @ $4

This is a call spread, so we add the net premium ($4) to the low strike ($60):

$60 + $4 = $64 breakeven

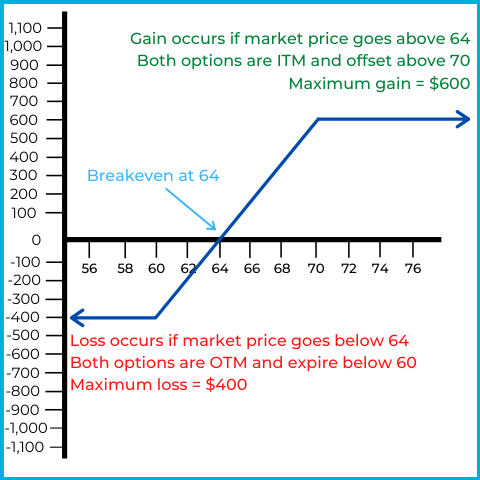

The options payoff chart summarizes the “big picture” of this long call spread. Here’s the position again:

Long 1 ABC Jan 60 call @ $8

Short 1 ABC Jan 70 call @ $4

Here’s the payoff chart:

The horizontal axis represents the market price of ABC stock, while the vertical axis represents overall gain or loss.

This investor is bullish, but they’ve capped their upside. Here’s how the spread behaves at different stock prices:

If ABC’s market price stays below $60

Both options are out of the money and expire worthless. The investor loses the original net debit, which is $400 (maximum loss).

If ABC’s market price goes above $60, but stays below $70

The long call is in the money and gains intrinsic value. At $64, the long call has $4 of intrinsic value ($64 − $60), which offsets the $4 net debit, so the position is at breakeven. Above $64, the investor profits as the long call gains more intrinsic value. The short call remains out of the money as long as the market stays below $70.

If ABC’s market price goes above $70

Both options are in the money. Above $70, gains on the long call are offset dollar-for-dollar by losses on the short call. The spread reaches maximum gain at $70, and the payoff stays capped above that level.

What was the investor’s intent?

They were bullish on ABC, but the long call’s premium ($800 total) was expensive. By selling the $70 call for $400, they reduce the net debit to $400. The trade-off is a “ceiling” at $70: no matter how high ABC rises, the short call offsets gains above $70.

Spreads can feel abstract at first because you’re combining two options with different strike prices. The key is to stay systematic: net premiums, net strikes, then use those results to find the max outcomes and breakeven.

Let’s try an example you can work through on your own:

An investor goes long 1 XYZ Dec 90 call at $6 and short 1 XYZ Dec 75 call at $13. Answer the following:

Maximum loss?

Maximum gain?

Breakeven?

Names of the spread?

Here are the answers:

This is how you can determine the answers:

Step 1: Net the premiums

Bought at $6 and sold at $13, creating a net credit of $7. Therefore, the maximum gain is $700.

Step 2: Net the strike prices

The difference between $75 and $90 is $15.

Step 3: Net strikes - net premium

$15 (net strikes) - $7 (net premium) = $8. This represents the “other max” not found in the first step. The maximum gain was determined in the first step, so the maximum loss is $800.

Step 4: Strike price +/- net premium

This is a call spread, so we add $7 (the net premium) to $75 (the low strike price). Therefore, the breakeven is $82.

Naming the spread

You can name this spread in two common ways. First, the short call has the higher premium, so it’s the dominant leg. Second, in a vertical call spread, the lower strike is the dominant leg, and here the lower strike ($75) is short. With the short call as the dominant leg, this spread is a:

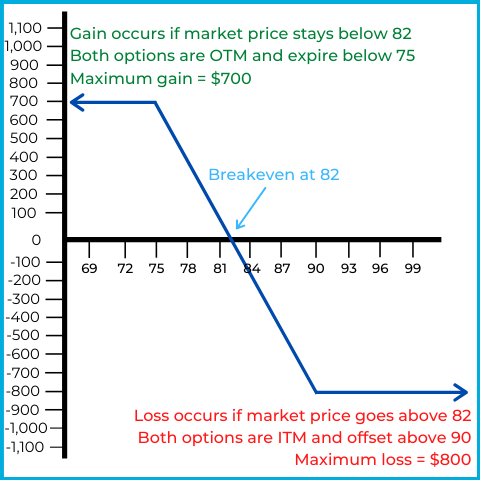

The options payoff chart summarizes the “big picture” of this short call spread. Here’s the position again:

Long 1 XYZ Dec 90 call @ $6

Short 1 XYZ Dec 75 call @ $13

Here’s the payoff chart:

The horizontal axis represents the market price of ABC stock, while the vertical axis represents overall gain or loss.

If XYZ’s market price stays below $75

Both options are out of the money and expire worthless. The investor keeps the original net credit, which is $700 (maximum gain). This is why it’s a bear call spread: the investor prefers the options to expire so they can keep the credit.

If XYZ’s market price goes above $75, but stays below $90

The short call is in the money and gains intrinsic value (which hurts a short option position). At $82, the short call has $7 of intrinsic value ($82 − $75), which offsets the $7 net credit, so the position is at breakeven. Above $82, the investor has an overall loss because the short call’s intrinsic value exceeds the credit received. The long call remains out of the money as long as XYZ stays below $90.

If XYZ’s market price goes above $90

Both options are in the money and begin offsetting each other. For every $1 the short call loses as the market rises, the long call gains $1. The long call caps the loss.

What was the investor’s intent?

They were bearish on ABC’s market price, but wanted a hedge in case of a bull market. Buying the $600 call reduces the net credit to $700 (from $1,300). The investor receives a lower premium, but the loss potential is capped if the market price rises above $90.

Math-based spread questions on the exam usually ask for maximum gain, maximum loss, or breakeven. You may also see questions that test how spreads behave when you close them before expiration. For example:

An investor goes long 1 CBA Sep 35 call at $9 and short 1 CBA Sep 45 call at $4. The market price goes to $43, and the investor closes the contracts at intrinsic value. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $300 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$900 |

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Close long call | +$800 |

| Close short call | $0 |

| Total | +$300 |

Initially, the investor buys the long call for $9 and sells the short call for $4, creating a net debit of $5 or $500 overall ($5 x 100 shares).

At $43, the long call is in the money (“call up”). To close the long call, the investor performs a closing sale equal to intrinsic value. The intrinsic value is $8 ($43 - $35), so the investor closes the long call by selling it for $800.

At $43, the short call is out of the money and has no intrinsic value. To close the short call, the investor performs a closing purchase equal to intrinsic value. The intrinsic value is $0, so the investor closes the short call by buying it for $0.

We have one last topic to cover in this chapter. Spread investors look for a specific outcome depending on whether the strategy is a debit or credit spread. Start with these associations:

In most cases, if you can identify whether the spread is a debit or credit spread, you can answer questions about the investor’s preferred outcome.

In a debit spread, the investor hopes for the spread between the option premiums to widen. For example:

Long 1 ZYX Jan 35 call @ $7

Short 1 ZYX Jan 45 call @ $2

Market price = $37

The spread between the premiums is currently $5 ($7 - $2). This is a bull call spread (the long call has the higher premium and lower strike price), so the investor wants ZYX’s market price to rise.

If the market price rises to $45, the long call’s premium will be at least $10, representing its intrinsic value. At $45, the short call still does not have intrinsic value (it’s out of the money). Assume the long call’s premium is now $10 and the short call’s premium stays at $2. The spread between the premiums is now $8 ($10 - $2), which is wider than the original $5 spread. With a wider premium spread, the investor can close the contracts at a profit.

In a debit spread, the investor also hopes for the options to exercise. Using the same structure:

Long 1 ZYX Mar 35 call @ $7

Short 1 ZYX Mar 45 call @ $2

Market price = $37

If both options expire worthless, the investor loses the original $500 net debit (the maximum loss). That happens if ZYX’s market price falls to or below $35.

If ZYX’s market price rises above $35, the long call goes in the money, gains intrinsic value, and begins producing a return. Once the market price exceeds $45, the short call also goes in the money and starts offsetting the long call’s gains.

When both options are in the money (above $45), the spread is at its maximum gain. Gains above $45 are negated by the short call, but the investor still achieves the capped maximum gain if both options are exercised.

For our last example, here’s how credit spreads show up in a question that doesn’t give premiums:

An investor goes long 1 LMN Jun 80 call and short 1 LMN Jun 65 call. Which of the following outcomes is the investor hoping for?

A) Spread between the premiums to widen and both options exercised

B) Spread between the premiums to narrow and both options expire

C) Spread between the premiums to widen and both options expire

D) Spread between the premiums to narrow and both options exercised

Answer = B (narrow & expire)

Premiums aren’t provided, but you can still identify the dominant leg in a vertical call spread by looking at the lower strike price. The $65 call is the lower strike, and it’s short, so the spread is a:

Once you know it’s a credit spread, the preferred outcome is narrow & expire.

If LMN’s market price falls below $65, both options go out of the money and have no intrinsic value. As both premiums approach $0, the spread between them narrows.

When the market price is below the low strike price ($65), both options expire worthless, locking in the investor’s maximum gain. That’s why the investor prefers expiration.

Whether you work through the full context or not, these are the primary test points to remember:

Some people use memory tricks here. For example, “credit,” “narrow,” and “expire” all have six letters, so the six-letter words go together.

If you’re more of a visual learner, here’s a video combining all we’ve covered on call spreads:

Sign up for free to take 12 quiz questions on this topic