Short straddles are essentially the opposite of long straddles. In the previous chapter, we learned that long straddles tend to be profitable when the market is volatile. Short straddles, by contrast, tend to be profitable when the market is flat (neutral).

These are the components of a short straddle:

Short call & short put*

*Must be the same strike price and expiration

For example:

Short 1 ABC Jan 60 call

Short 1 ABC Jan 60 put

A short call creates an obligation to sell shares, while a short put creates an obligation to buy shares.

By selling both options, the investor is betting on market neutrality (little to no price movement).

If the stock’s market price stays flat, both options may expire worthless. That happens when ABC’s market price is exactly the shared strike price. This is the best-case scenario for a short straddle.

If the stock’s market price rises, the call will be assigned (exercised). This is the highest-risk direction because the short call obligates the investor to sell shares at the strike price. If the investor doesn’t already own the shares, they must buy them at the market price first. The higher the market price rises, the more expensive it is to acquire the shares, and the larger the loss.

If the stock’s market price falls, the put will be assigned (exercised). This also creates significant risk because the short put obligates the investor to buy shares at the strike price. The further the market price falls, the more the investor overpays relative to the market price, and the larger the loss.

A short straddle is a risky strategy because it involves two naked (uncovered) options. The investor does receive two premiums up front, though. That means losses must exceed the combined premiums before the position produces an overall loss. In general, the investor profits when the stock’s market price doesn’t move dramatically.

Let’s take a look at several scenarios to understand short straddles better:

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market rises to $120?

Can you figure it out?

Answer = $5,100 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Buy shares | -$12,000 |

| Call assigned - sell shares | +$6,000 |

| Total | -$5,100 |

At $120, the call is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the put is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value). The put expires worthless, but the call is assigned (exercised), so the investor must fulfill the obligation to sell.

To deliver shares at $60, the investor buys stock in the market at $120 and then sells at $60. That creates a $60 loss per share, or $6,000 total ($60 x 100 shares). The $900 combined premium received up front reduces the loss to $5,100.

The investor wanted a flat market, but the stock moved sharply upward. Even though only one option finished in the money, the short call produced a large loss. The premiums offset part of that loss, but the overall result is still substantial.

The maximum loss for a short straddle is unlimited. The further the market rises, the larger the loss because of the short naked call.

What happens if the market rises a moderate amount?

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price rises to $69?

Answer = $0 (breakeven)

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Buy shares | -$6,900 |

| Call assigned - sell shares | +$6,000 |

| Total | $0 |

At $69, the call is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the put is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value). The put expires worthless, but the call is assigned (exercised), so the investor must sell shares at $60.

The investor buys stock at $69 and sells at $60, creating a $9 loss per share, or $900 total ($9 x 100 shares). The $900 combined premium received up front offsets that loss, resulting in breakeven.

$69 is one of two breakevens for this example (we’ll discuss the other breakeven later). On the upside, the short call must lose an amount equal to the combined premiums for the overall position to break even. So the upside breakeven is the strike price plus the combined premium: $60 + $9 = $69.

What happens if the market rises slightly?

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price rises to $64?

Answer = $500 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Buy shares | -$6,400 |

| Call assigned - sell shares | +$6,000 |

| Total | +$500 |

At $64, the call is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the put is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value). The put expires worthless, but the call is assigned (exercised).

The investor buys stock at $64 and sells at $60, creating a $4 loss per share, or $400 total ($4 x 100 shares). The $900 combined premium received up front more than offsets that loss, resulting in a $500 gain.

A short straddle benefits when the stock stays close to the shared strike price. Here, the stock rose by $4, but the assignment loss on the call didn’t exceed the combined premiums.

What happens if the market remains flat?

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price stays at $60?

Answer = $900 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Total | +$900 |

At $60, both options are “at the money” and expire worthless (contracts must have intrinsic value to be exercised). The investor keeps the entire $900 in combined premiums.

This is the best-case scenario because it produces the maximum gain.

The maximum gain for a short put can be found by using this formula:

What happens if the market falls a small amount?

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price falls to $59?

Answer = $800 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Put assigned - buy shares | -$6,000 |

| Share value | +$5,900 |

| Total | +$800 |

At $59, the put is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the call is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value). The call expires worthless, but the put is assigned (exercised), so the investor must buy shares at $60.

Those shares are worth $59 in the market, creating a $1 loss per share, or $100 total ($1 x 100 shares). The $900 combined premium received up front offsets the loss, resulting in an overall gain of $800.

Again, the key idea is that small moves away from the strike price can still be profitable as long as the intrinsic value on the in-the-money option doesn’t exceed the combined premiums.

What happens if the market falls a little further?

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price falls to $51?

Answer = $0 (breakeven)

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Put assigned - buy shares | -$6,000 |

| Share value | +$5,100 |

| Total | $0 |

At $51, the put is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the call is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value). The call expires worthless, but the put is assigned (exercised), so the investor must buy shares at $60.

Those shares are worth $51 in the market, creating a $9 loss per share, or $900 total ($9 x 100 shares). The $900 combined premium received up front offsets the loss, resulting in breakeven.

$51 is the other breakeven for this example. On the downside, the short put must lose an amount equal to the combined premiums for the overall position to break even. So the downside breakeven is the strike price minus the combined premium: $60 - $9 = $51.

Here’s the general formula for breakeven on straddles:

The breakeven formula is the same for both long and short straddles.

Straddles are one of the only options strategies with multiple breakevens. To find both quickly, first add up the combined premiums. Next, add and subtract the combined premiums to and from the shared strike price. In summary, the two breakevens for this short straddle are $51 and $69.

What happens if the market falls significantly?

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price falls to $25?

Answer = $2,600 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Put assigned - buy shares | -$6,000 |

| Share value | +$2,500 |

| Total | -$2,600 |

At $25, the put is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the call is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value). The call expires worthless, but the put is assigned (exercised), so the investor must buy shares at $60.

Those shares are worth $25 in the market, creating a $35 loss per share, or $3,500 total ($35 x 100 shares). The $900 combined premium received up front reduces the loss to $2,600.

The investor wanted a flat market, but the stock moved sharply downward. Even though only one option finished in the money, the short put produced a large loss. The premiums offset part of that loss, but the overall result is still substantial.

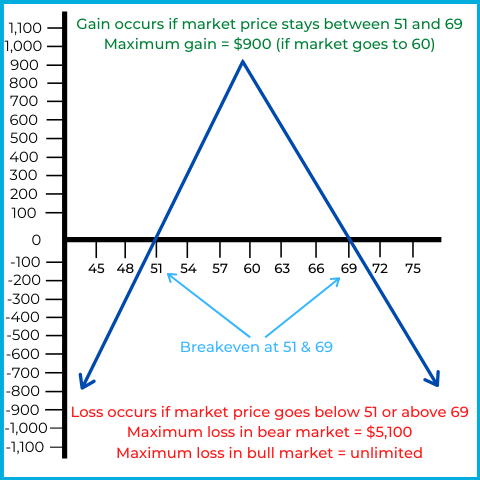

Let’s look at the options payoff chart to summarize the big picture for this short straddle. First, let’s re-establish the example:

Short 1 ABC Jan 60 call @ $4

Short 1 ABC Jan 60 put @ $5

Here’s the payoff chart:

The horizontal axis represents the market price of ABC stock, while the vertical axis represents overall gain or loss.

As the short straddle payoff chart shows, the investor reaches their maximum gain of $900 at a market price of $60. At that price, both options expire worthless, and the combined premiums are the overall gain.

If the market price rises above or falls below $60, the call or the put goes “in the money” and gains intrinsic value. Remember, option writers (sellers) experience losses when their contracts gain intrinsic value. Intrinsic value benefits the holder (buyer, long side) and hurts the writer (seller, short side).

In our last few examples, let’s explore what happens if investors close out contracts at intrinsic value. As we’ve learned previously, closing out contracts means trading the contracts instead of waiting for assignment or expiration.

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. ABC’s market price falls to $40 and the investor closes the contracts at intrinsic value. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $1,100 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Close call | $0 |

| Close put | -$2,000 |

| Total | -$1,100 |

At $40, the put is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the call is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value).

The investor received $9 in premium up front and pays $20 to close the put, creating an $11 loss per share, or $1,100 total ($11 x 100 shares).

As a reminder, closing a position means doing the opposite of the opening transaction. Here, both options were sold to open the short straddle (opening sales), so both must be bought to close (closing purchases). After selling $900 of options and buying to close for $2,000, the investor ends with a $1,100 loss.

Let’s examine one more scenario involving closing transactions for our last example:

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. ABC’s market price rises to $67 and the investor closes the contracts at intrinsic value. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $200 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Close call | -$700 |

| Close put | $0 |

| Total | +$200 |

At $67, the call is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the put is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value).

The investor received $9 in premium up front and pays $7 to close the call, creating a $2 gain per share, or $200 total ($2 x 100 shares).

As in the previous example, both options were sold to open the short straddle (opening sales), so both must be bought to close (closing purchases). After selling $900 of options and buying to close for $700, the investor ends with a $200 gain.

This video covers the important concepts related to short straddles:

For suitability, short straddles should only be recommended to aggressive options traders with a substantial net worth when a flat market is expected. If volatility appears unexpectedly, the investor is exposed to unlimited risk. In general, the fewer assets an investor has, the less appropriate it is to sell straddles.

Sign up for free to take 11 quiz questions on this topic