Cell biology of cancer

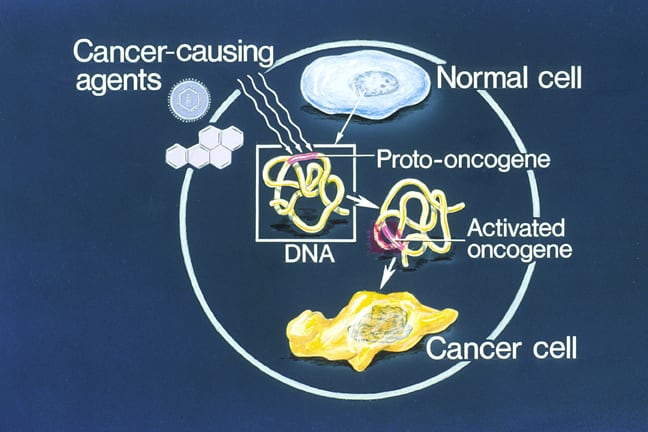

Cell biology of cancer: Proto-oncogenes are normal cellular genes involved in cell division, cell differentiation, and cell death. Mutations in proto-oncogenes can convert them into oncogenes, which drive dysregulated growth, differentiation, and cell death, leading to cancer (oncogenesis).

Proto-oncogene mutations can increase gene activity or expression in several ways:

- Mutations that create a hyperactive gene product

- Promoter region mutations that increase transcription

- Gene amplification

- Chromosomal translocations that increase expression (e.g., the Philadelphia chromosome)

Mutations in tumor suppressor genes can also cause cancer, typically through loss of function. In contrast to oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes normally repress cell growth and division.

A key genetic difference is how many gene copies must be affected:

- Tumor suppressor genes: both copies must be mutated or lost (they behave recessively) for oncogenesis

- Proto-oncogenes/oncogenes: mutation in only one copy is sufficient (they behave dominantly) for oncogenesis

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, single-stranded, endogenous RNAs that are 21-25 nucleotides long. They are encoded by non-coding or intronic regions of genes and are not translated into proteins. Upregulation or downregulation of miRNAs occurs in various human cancers.

miRNAs affect the expression of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. They bind to target mRNAs, leading to translational repression and gene silencing.

Accumulation of genetic mutations over time, along with DNA damage, can eventually cause cancer. The clonal evolution model of oncogenesis states that accumulated mutations within a single genetically transformed cell confer oncogenic potential, and that cell then multiplies to form a clone of cancer cells. These cells become insensitive to growth-inhibitory signals, resist apoptosis, and sustain growth through angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis.

The stem cell theory of cancer states that cancers arise from stem cells, which are self-renewing, more aggressive, and resistant to therapy.

Undifferentiated tumor cells are less cohesive. During tumor invasion:

- E-cadherin is downregulated, reducing cell-to-cell adhesion

- Tumor cells separate from the primary tumor

- Tumor cells degrade the extracellular matrix by secreting enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases and collagenases

- Tumor cells enter blood vessels and lymphatics and are carried to distant sites

Angiogenesis (new blood vessel formation) is promoted by secretion of VEGF, which supports tumor growth. Circulating tumor cells may aggregate to form tumor emboli. Extravasation of tumor cells is aided by metalloproteinases and the permeability protein angiopoeitin-like 4.

Some tumors express chemokine receptors such as CXCR4, which help them localize to favorable organs rich in specific receptor ligands. The primary tumor can also prime other tissues for tumor seeding by secreting growth factors such as VEGF and TGF beta.

Micrometastases are small numbers of cancer cells that have spread from the primary tumor to other parts of the body but are too few to be detected by screening or diagnostic tests. They are associated with a higher risk of recurrence.

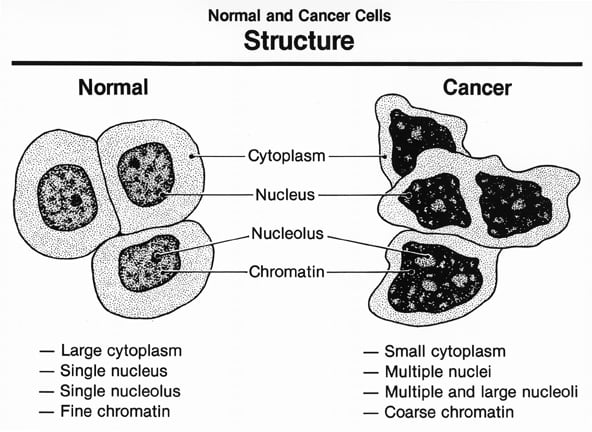

Tumor grading and staging: Tumor grading measures how differentiated tumor cells are. The higher the grade, the more undifferentiated the tumor. Differentiated tumors resemble their cell and tissue of origin, while undifferentiated (anaplastic) tumors do not. Grading is determined by tumor biopsy. The following grades are reported:

GX: Grade cannot be assessed (undetermined grade)

G1: Well differentiated (low grade)

G2: Moderately differentiated (intermediate grade)

G3: Poorly differentiated (high grade)

G4: Undifferentiated (high grade)

Higher-grade tumors are more aggressive and tend to spread faster. The Gleason scoring system is used to grade prostate cancer. A score <6 is well differentiated, while a score >8 is poorly differentiated.

Tumor stage describes the extent of tumor spread. Staging helps predict prognosis and guides therapeutic decisions. The TNM system is most commonly used.

T for tumor size and extent (TX for main tumor cannot be measured; T0 for main tumor cannot be found; T1, T2, T3, T4 for progressively increasing size).

N for presence or absence of lymph node metastases (NX, N0, N1, 2, or 3).

M for distant metastases (MX, M0, and M1).

Stage 0: Abnormal cells are present but have not spread to nearby tissue. Also called carcinoma in situ (CIS).

Stage I, Stage II, and Stage III: The higher the number, the larger the tumor and the more it has spread into nearby tissues.

Stage IV: The cancer has spread to distant parts of the body.