Combinations are similar to straddles, but the two options have different strike prices, different expiration dates, or both.

Here’s a quick refresher on a straddle:

Long 1 ABC Jan 70 call

Long 1 ABC Jan 70 put

A long straddle uses two long options (one call and one put) with the same expiration and the same strike price. Change either the strike price or the expiration, and you’ve created a long combination.

For example, different strike prices:

Long 1 ABC Jan 80 call

Long 1 ABC Jan 70 put

This is no longer a straddle because the strike prices differ.

Different expirations:

Long 1 ABC Jan 70 call

Long 1 ABC Feb 70 put

This is a combination because the expirations differ.

Different strikes and expirations:

Long 1 ABC Jan 80 call

Long 1 ABC Feb 70 put

Bottom line: if it looks like a straddle but the strikes, expirations, or both don’t match, it’s a combination.

Long straddles profit in volatile markets and lose in flat markets. The investor profits if the gain on the call or put is greater than the total premiums paid. Long combinations work the same way.

Let’s work through some math-based combination questions.

An investor goes long 1 ABC Jan 80 call at $3 and long 1 ABC Jan 70 put at $2 when ABC’s market price is $75. What is the maximum gain?

Maximum gain = unlimited

Like a long straddle, the long call provides unlimited upside if the stock rises. In a strong up move, the put expires, but the call’s value can keep increasing as ABC’s market price rises.

The call gives the right to buy ABC at $80. If the market price rises above $80, the investor can buy at $80 and sell at the higher market price.

How about maximum loss?

An investor goes long 1 ABC Jan 80 call at $3 and long 1 ABC Jan 70 put at $2 when the market price is $75. What is the maximum loss?

Maximum loss = $500 (premiums)

As with a long straddle, the most the investor can lose is the total premium paid.

The key difference from a straddle is where that maximum loss occurs.

Why?

So this combination has a wider “dead zone” where both options can expire.

Before we move on, this specific combination is known as a strangle. A strangle is a combination where both options (long or short) are out of the money (have no intrinsic value) when the position is established.

Here’s the strategy again:

Long 1 ABC Jan 80 call @ $3

Long 1 ABC Jan 70 put @ $2

Market price = $75

At $75:

If the market stays at $75 through expiration, both options expire worthless:

A strangle is sometimes called a “cheap person’s straddle” because it typically costs less than a straddle (lower premiums), but the stock has to move farther for either option to become in the money.

Let’s find the breakevens.

An investor goes long 1 ABC Jan 80 call at $3 and long 1 ABC Jan 70 put at $2 when ABC’s market price is $75. What is the breakeven?

Breakevens = $65 and $85

Like a straddle, a combination has two breakevens - one on the downside and one on the upside.

First, add the premiums:

Then:

You can also see this using intrinsic value:

To find the breakevens on a combination, add the premiums, subtract the total from the put strike, and add the total to the call strike.

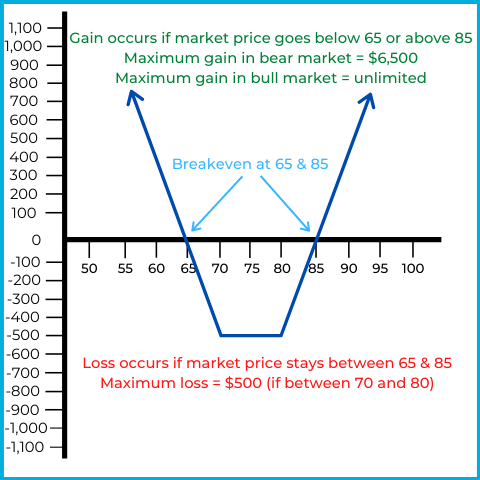

Let’s use the payoff chart to summarize the big picture for this long combination. Here’s the position again:

Long 1 ABC Jan 70 put @ $2

Long 1 ABC Jan 80 call @ $3

Here’s the payoff chart:

The horizontal axis represents the market price of ABC stock, while the vertical axis represents overall gain or loss.

As the chart shows:

At the breakevens:

Above $85, the position is profitable with unlimited upside potential (because of the long call). Below $65, the position is profitable with downside profit potential up to $6,500 (which would occur if ABC fell to $0: $65 × 100 shares).

Let’s move on to short combinations.

Short straddles profit in flat markets and lose in volatile markets. If the stock moves too far up or down, assignment losses can exceed the premiums received. Short combinations behave the same way.

Let’s go through some short combination questions.

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 40 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 30 put at $3 when ABC’s market price is $35. What is the maximum gain?

Maximum gain = $700 (premiums)

For short option strategies, the maximum gain is the premium received.

The investor earns the maximum gain if both options expire worthless.

Compared to a short straddle, this short combination has a wider range where both options can expire:

So if ABC finishes between $30 and $40, both options expire and the investor keeps the full premium.

How about the maximum loss?

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 40 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 30 put at $3 when ABC’s market price is $35. What is the maximum loss?

Maximum loss = unlimited

Short straddles and short combinations both have unlimited risk because of the short (naked) call.

If ABC rises above $40:

As the market price rises, the cost to buy shares rises without limit, so the loss is unlimited.

The short put can also create large losses if ABC falls sharply, but the short call is what creates unlimited risk.

For our last question, let’s find the breakevens.

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 40 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 30 put at $3 when ABC’s market price is $35. What is the breakeven?

Breakevens = $23 and $47

Short combinations also have two breakevens. Here, the investor breaks even when assignment losses equal the premium received.

First, add the premiums:

Then:

You can see this in dollar terms:

To find the breakevens on a combination (long or short), add the premiums, subtract the total from the put strike, and add the total to the call strike.

Sign up for free to take 15 quiz questions on this topic