Suitability

Benefits

The primary benefit of bonds is interest income. Most bonds pay interest semiannually, and those interest payments are a legal obligation of the issuer. Unlike cash dividends on stock, interest payments don’t require approval from the Board of Directors (BOD). That’s why bond income is usually more predictable.

Capital appreciation (growth) can also occur, especially when interest rates fall. However, interest rate movements are hard to predict, and bonds mature at par. If you hold a bond to maturity, you’ll receive the face (par) value back at maturity. For that reason, most bond investors don’t buy bonds primarily for price appreciation unless the bond is convertible (covered later).

Bond prices are often less volatile than stock prices, though this isn’t always true. Because interest is a legal obligation and isn’t tied to the company’s profitability, bond price swings are often milder. Major price moves can still happen, especially when interest rates change sharply or when an issuer is close to bankruptcy.

Systematic risks

Investing in bonds involves several risks. Some are specific to bonds, and others apply to many types of investments. We’ll start with systematic risks, which affect the overall market and can’t be eliminated through diversification.

Interest rate risk

We discussed price volatility earlier in this unit. That volatility is closely tied to interest rate risk.

- Bonds with long maturities and low coupons tend to move the most when market conditions change.

- The biggest driver of bond prices is changes in interest rates.

Interest rate risk shows up when interest rates rise. When rates rise, existing bond prices fall. The reason is competition: newly issued bonds come to market with higher coupons, so older bonds must drop in price to offer a competitive yield.

Most bonds have fixed interest rates, but variable rate bonds exist (covered later). Their coupons reset periodically (often monthly or semiannually) based on interest rate changes, which helps keep their market values more stable. As a result, variable rate securities generally avoid interest rate risk.

Interest rate risk applies to all fixed income investments, including preferred stock.

Inflation (purchasing power) risk

We introduced inflation risk in the preferred stock chapter. Inflation (purchasing power) risk occurs when prices of goods and services rise more than expected. Inflation is normal in an economy, but unexpected spikes can be especially damaging to bonds. Remember our story about Zimbabwe in 2008? We also saw the impacts of inflation in the US from 2021-2023.

Bonds are particularly exposed to inflation risk because their coupons are usually fixed. You receive a fixed dollar amount of interest over the bond’s life. If prices rise significantly (milk, cars, real estate, and everything else), those fixed interest payments buy less.

The US Government bond chapter will cover how the Federal Reserve manages inflation. For now, the key point is that the Fed tends to raise interest rates when inflation rises. That’s why purchasing power risk and interest rate risk are closely connected.

Like interest rate risk, purchasing power risk increases with maturity: the longer the bond’s maturity, the more purchasing power risk it generally has. One common way to reduce inflation exposure is to use short-term bonds. When they mature sooner, you can reinvest the proceeds at current (potentially higher) interest rates instead of being locked into a lower rate for a long time.

Reinvestment risk

Interest rate changes create risk in both directions. Reinvestment risk occurs when interest rates fall.

When interest rates fall, bond prices rise - but reinvestment risk focuses on what happens to cash flows you need to reinvest. Long-term investors often keep money invested continuously. When a bond pays interest, you may reinvest that interest by buying another security (or more of the same one). If rates have fallen, that reinvestment typically happens at lower yields.

Bonds with the highest and most frequent interest payments have the most reinvestment risk. In the US Government bond chapter, you’ll learn about mortgage-backed securities, which make monthly payments. Because payments arrive so frequently, there’s more cash to reinvest, which increases reinvestment risk.

Conversely, zero coupon bonds have essentially no reinvestment risk. If a bond doesn’t pay ongoing interest, there’s nothing to reinvest.

Earlier in this unit, we learned about callable bonds. Call risk is a type of reinvestment risk. Bonds are most likely to be called when interest rates fall, because issuers can refinance by issuing new bonds at lower rates. Call risk is often considered the worst form of reinvestment risk: you don’t just reinvest interest at lower rates - you may also have to reinvest your principal.

Non-systematic risks

Now we’ll cover non-systematic risks, which affect a single investment or a small part of the market. These risks can be largely eliminated through diversification.

Default risk

Default risk (also called credit risk or repayment risk) is the risk that an issuer can’t make required interest and/or principal payments. The most common cause is bankruptcy.

Bankruptcy isn’t common, but it does happen. Corporations - and sometimes governments - can default (government defaults are rare). For example, the city of Detroit declared bankruptcy and defaulted on its bonds in 2013. It was (and still is) the largest default by a municipal (local government) issuer in US history. If you held Detroit bonds at that time, you likely lost substantial money.

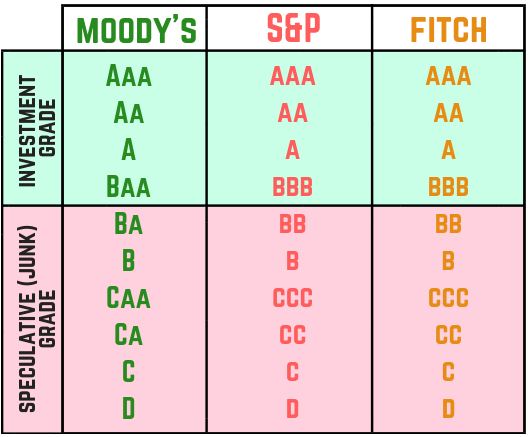

Rating agencies help investors estimate a bond’s default risk. The three rating agencies to know for the exam are Standard & Poors (S&P’s), Moody’s, and Fitch. Their rating symbols differ slightly, but they all focus on default risk. Here’s how their ratings appear:

You don’t need to memorize every rating, but you do need to distinguish between investment grade and speculative grade bonds:

- Investment grade bonds have little-to-no default risk and are rated BBB or higher.

- Speculative grade bonds (also called junk bonds) have considerable default risk and are rated BB or lower.

Liquidity (marketability) risk

Liquidity (marketability) risk is the risk that a security can’t be sold quickly, or can only be sold with a deep discount. Some investments have higher liquidity risk than others. For example, municipal bonds are known for liquidity risk, and we’ll cover why in a future chapter.

In general, the less desirable a bond is to investors, the more liquidity risk it has. For example, a bond from a company near bankruptcy may be difficult to sell without a steep price discount (or may not be sellable at all).

Legislative risk

Legislative risk is the risk that a new law or regulation negatively affects an investment. For example, the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration in 2018 increased the cost of doing business with foreign companies from certain countries. Investors experienced legislative risk when the stock market responded negatively to the trade war.

Political risk

Political risk occurs when political instability negatively affects an investment. Examples include military coups, threats or acts of war, and mass riots. Political risk can occur anywhere, but it most often affects foreign securities from countries with unstable government structures.

The PRS Group political risk index ranked the United States as the second safest for political risk within the listed countries in the North American and Central American region (Canada was first) and 19th overall. While the US political arena has been volatile for the last several years, it has not significantly impacted the stock market (example 1, example 2).

Typical investor

Many types of bonds are available, and they come with different risks and benefits. This section describes the typical bond investor in general terms.

Compared with stock investors, bond investors are often older and more conservative. Because interest payments are a legal obligation of the issuer, bonds usually involve less risk than stocks, which generally means lower expected returns. Investors who want safer, more predictable income often prefer debt securities over equity (stock) securities.

That said, not all bonds are low-risk. Some bonds carry substantial risk. For example, junk bonds offer higher yields, but investors can lose significant money if a default occurs.

As discussed above, interest income is the main reason most investors buy bonds. If an investor isn’t seeking income, another asset class may be a better fit. One exception is zero coupon bonds, which pay interest only at maturity. If an investor wants a predictable payout years in the future but doesn’t need income along the way, a long-term zero coupon bond could be suitable.