Yield

We first discussed the concept of yield in the preferred stock chapter. The idea is the same for bonds: yield measures the overall return of an investment. For bonds, yield is influenced by several factors, including:

- The interest rate (coupon)

- The purchase price

- The length of time until maturity

A bond’s interest rate (coupon) and its yield sound similar, but they aren’t the same thing (except for nominal yield, discussed below). The interest rate is the annual interest the issuer pays based on par value. Yield is the bond’s overall rate of return, which depends on both the coupon and the price you pay. If a bond is purchased at a discount or a premium, its yield will differ from its coupon.

We’ll discuss the following yields in this chapter:

- Nominal yield

- Current yield

- Yield to maturity (YTM)

- Yield to call (YTC)

Nominal yield

The nominal yield is another name for the bond’s interest rate (coupon). You’ll rarely calculate nominal yield in practice, but you may be asked to identify the formula.

For example:

A $1,000 par, 4% bond

This calculation simply confirms the stated 4% coupon. Nominal yield depends on two values that don’t change:

- Par value ($1,000)

- Annual interest paid ($40)

No matter what happens to the bond’s market price, the issuer still pays $40 per year, and the bond still matures at $1,000. That’s why nominal yield stays fixed over the bond’s life. Unlike the other yields in this chapter, market price is not part of the nominal yield calculation.

Current yield

A bond’s current yield is a quick (but incomplete) way to estimate return. It uses annual income and the bond’s current market price, but it ignores time. Time matters for bonds because it affects:

- How long you receive interest payments

- When you receive the principal repayment

Because of that, current yield is often used as a fast approximation, but it can be misleading if treated as a full measure of return.

Let’s add market price to the example.

A $1,000 par, 4% bond bought for $800

If this bond is bought at $800 (a discount), the investor’s overall return will be higher than the 4% coupon. That’s because the investor earns return from two sources:

Coupon

- Pays the investor $40 annually

Discount

- Investor earns $200 over the life of the bond

The investor receives 4% of par ($1,000) each year, and also benefits from the bond moving from the purchase price ($800) up to par ($1,000) at maturity. That extra $200 increases the overall return.

Current yield is calculated by dividing annual income by the bond’s market price.

A $1,000 par, 4% bond bought for $800. What’s the current yield?

Can you figure it out?

Because the bond is purchased at a discount, the current yield (5%) is higher than the coupon (4%). So you can assume:

- For discount bonds, current yield > coupon

Now compare that to a premium bond. Premium bonds trade above par.

A $1,000 par, 4% bond bought for $1,100

The investor still receives $40 per year in interest. But because the bond matures at par, paying $1,100 for a bond that will be worth $1,000 at maturity creates a $100 loss over time. That pushes the overall return below the coupon.

A $1,000 par, 4% bond bought for $1,100. What is the current yield?

Can you figure it out?

Here, the current yield (3.6%) is lower than the coupon (4%). So you can assume:

- For premium bonds, current yield < coupon

Here’s a video breakdown of a practice question on current yield:

Yield to maturity (YTM)

Yield to maturity and yield to call formulas are difficult to memorize and typically are not tested. Exam questions are more likely to focus on the relationships of the yields, which is best depicted on the bond see-saw (discussed at the end of this chapter). Additionally, a test question may focus on the components of these yield formulas. Don’t spend much time focusing on the math related to these yields.

Unlike current yield, yield to maturity (YTM) (also called a bond’s basis) includes time. It assumes the investor buys the bond and holds it until maturity, making it a more complete measure of overall return.

A 10 year, $1,000 par, 4% bond is trading at $800. What is the yield to maturity (YTM)?

Here’s what each part represents:

- Annual income is $40 (4% of $1,000 par).

- The total discount is $200 ($1,000 − $800). Spread over 10 years, that’s $20 per year.

- The denominator uses the average of price and par: ($800 + $1,000) / 2 = $900.

The YTM (6.7%) is higher than the coupon (4%). That matches the general pattern: discount bonds have yields above the coupon because the discount adds to return.

Now compare a premium bond.

A 10 year, $1,000 par, 4% bond is trading at $1,100. What is the yield to maturity (YTM)?

- Annual income is still $40.

- The total premium is $100 ($1,100 − $1,000). Spread over 10 years, that’s $10 per year.

- We subtract the annualized premium because it reduces return.

- The average of price and par is ($1,100 + $1,000) / 2 = $1,050.

The YTM (2.9%) is lower than the coupon (4%), which is the typical premium-bond relationship.

Yield to call (YTC)

Remember the advice above - the math behind the yield to call formula is unimportant.

Yield to call (YTC) applies only to callable bonds. If a bond isn’t callable, there is no YTC.

YTC is the bond’s overall rate of return assuming it’s called at the first call date. Like YTM, it includes time. The formula is similar to YTM, but it uses:

- The call price instead of par at maturity

- The years to call instead of years to maturity

A 10 year, $1,000 par, 4% bond is trading at $800. The bond is callable at par after 5 years. What is the yield to call (YTC)?

The YTC (8.9%) is higher than the coupon (4%), and it’s also higher than the YTM (6.7%). The reason is timing: the investor earns the $200 discount sooner.

- Held to maturity: the $200 discount is realized over 10 years.

- Called in 5 years: the same $200 is realized in 5 years, increasing the annualized return.

Now look at a premium bond.

A 10 year, $1,000 par, 4% bond is trading at $1,100. The bond is callable at par after 5 years. What is the yield to call (YTC)?

The YTC (1.9%) is lower than the coupon (4%), and it’s also lower than the YTM (2.9%). Again, timing explains it:

- Held to maturity: the $100 premium is lost over 10 years.

- Called in 5 years: the same $100 loss happens in 5 years, reducing the annualized return.

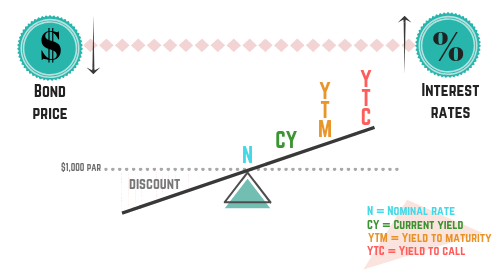

Discount bond yield relationships

Let’s summarize the discount bond example from the previous sections.

A 10 year, $1,000 par, 4% bond is trading at $800. The bond is callable at par after 5 years.

-

Coupon = 4.0%

-

Current yield = 5.0%

-

YTM = 6.7%

-

YTC = 8.9%

This ordering is consistent for discount bonds:

- Coupon is the lowest

- Then current yield

- Then YTM

- Then YTC

Instead of calculating each yield, many test-takers rely on a visual tool: the bond see-saw.

The bond see-saw is a fast way to determine how price relates to yields. Many people memorize it and rewrite it on scratch paper at the start of the exam.

FINRA is more focused on whether you understand which yield is higher or lower than on whether you can compute every yield. You may still need to calculate current yield, but yield relationships are tested frequently. Knowing the order also helps you eliminate incorrect answer choices.

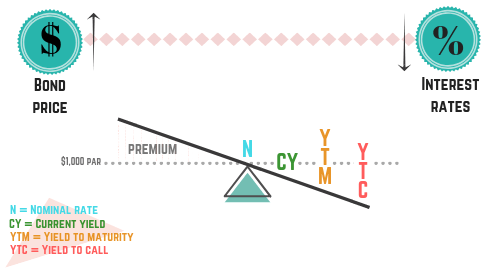

Premium bond yield relationships

Let’s continue using the premium bond example from the previous sections.

A 10 year, $1,000 par, 4% bond is trading at $1,100. The bond is callable at par after 5 years.

-

Coupon = 4.0%

-

Current yield = 3.6%

-

YTM = 2.9%

-

YTC = 1.9%

This ordering is consistent for premium bonds:

- YTC is the lowest

- Then YTM

- Then current yield

- Then coupon

You can calculate each yield, or you can use the bond see-saw.

For premium bonds, the price side points upward because the bond trades above par. The yield side points downward, reflecting that yields are below the coupon.

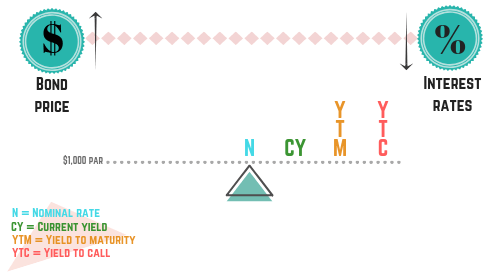

Yield for par bonds

We’ve seen how discounts and premiums affect yield. What if a bond is purchased at par ($1,000)? This case is straightforward.

When a bond is purchased at par:

- The bond is bought at $1,000 and matures at $1,000.

- There is no gain or loss from price movement back to par.

- The only return is the coupon.

So, all yields equal the coupon.

For a bond purchased at par, the see-saw looks like this:

Coupon, current yield, YTM, and YTC all line up at the same level. If you see a question about par bond yields, keep it simple: they’re all the same.

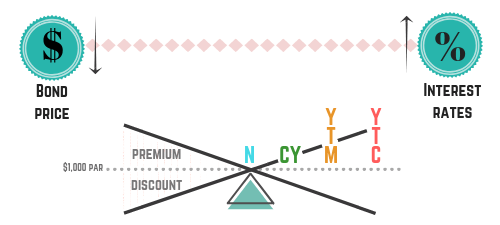

The bond see-saw

Yield is a major SIE topic, and the bond see-saw helps you visualize the relationship between bond prices, interest rate changes, and yields. Here are the discount, premium, and par versions together:

If you use a “dump sheet,” this is a common item to include. A dump sheet is a set of key visuals or facts you write on scratch paper after the exam begins, so you can reference them during questions.

Some test-takers also use acronyms like this:

CYM Call

-

CY = Current Yield

-

M = yield to Maturity

-

Call = yield to Call

Use any memory aid that helps you keep the yield terms and their order straight.