Collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs) aren’t products of federal agencies, but they’re closely tied to them. Earlier, we saw how the mortgage agencies (Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac) buy mortgages from private lenders and package them into pass through certificates. Two unique risks come with these securities: prepayment risk and extension risk. CMOs were created to reduce these risks and make mortgage-backed securities more predictable.

When you invest in a pass through certificate, the timing of your principal return can change a lot.

If interest rates fall, homeowners often refinance and pay off their mortgages early. That means the pass through certificate pays back principal faster than expected. For example, an expected 15-year maturity could turn into a 5-year maturity. The investor then has to reinvest that principal at lower market rates (because rates fell). This is prepayment risk.

If interest rates rise, homeowners are less likely to refinance or pay off a low-rate mortgage early. That slows principal payments, extending the life of the pass through certificate. For example, an expected 15-year maturity could stretch to 25 years. The investor is then locked into a lower-yielding investment for longer. This is extension risk.

CMOs reduce these risks by changing how principal is distributed. Unlike pass through certificates, CMOs don’t pass principal payments through to investors on a pro-rata basis.

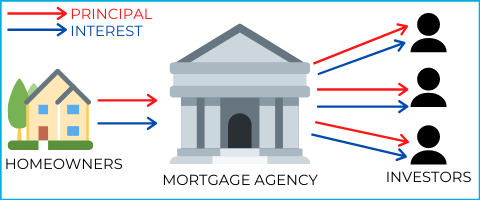

CMOs are essentially “sliced up” pass through certificates. Here’s a visual of a pass through certificate:

Homeowners make monthly principal and interest payments to the mortgage agency (Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, or Freddie Mac), and the agency then “passes through” those payments to investors.

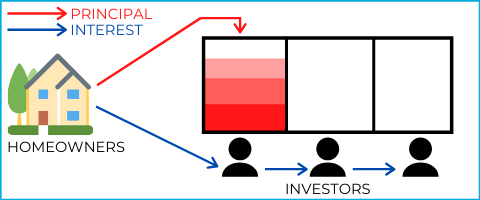

CMOs are created by financial institutions that typically buy pass through certificates from the agencies and repackage them. The pass through certificate is divided into tranches.

A simple CMO structure looks like this:

These are plain vanilla CMO tranches.

A structure like this can still face prepayment and extension risk, but investors have more clarity about where they stand.

Tranches are chosen based on how long an investor wants payments to last and how much risk they’re willing to accept.

In practice, CMOs can have hundreds or even thousands of tranches.

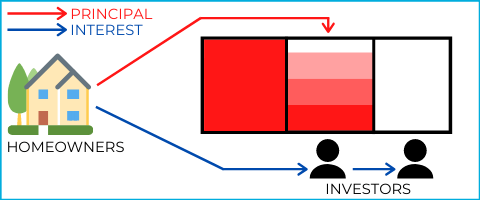

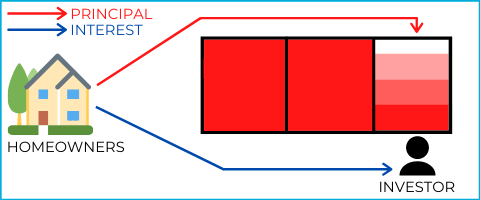

Once the first tranche receives all of its principal, that tranche is retired (it has matured). Interest continues to be paid to the remaining tranches on a pro-rata basis, but principal now moves to the next tranche in the sequence.

After the second tranche is fully paid off, it’s retired as well. Principal then flows to the final tranche, which receives the remaining principal (and continues receiving its share of interest).

Choosing the right tranche can be challenging because payment speed depends on economic factors like interest rates and housing market conditions. Investors often use forecasting tools to estimate how quickly principal will be paid.

Formerly known as the Public Securities Association, the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) publishes a prepayment speed assumption (PSA) that investors use to estimate how quickly tranches may be retired.

Tools used to estimate prepayment speeds can be complex. The Series 7 generally doesn’t test the mechanics. The key point is that some investors use SIFMA’s PSA assumptions to forecast how quickly a tranche may be paid off.

Plain vanilla tranches aren’t the only tranche types you may see.

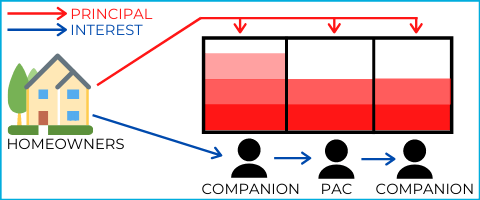

Planned amortization class (PAC) CMOs use other tranches called companion classes to absorb variability in principal payments.

Here’s the basic idea:

Although this looks similar to a plain vanilla structure, the key difference is how principal is managed.

Because companion classes exist to protect the PAC, they’re generally riskier.

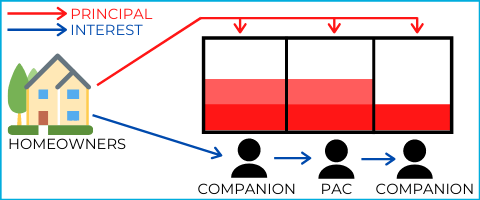

The back-end companion class becomes important when extension risk occurs (principal arrives slower than expected):

In this scenario:

This structure helps the PAC receive principal closer to the forecasted schedule. In short, PACs use companion classes to reduce both prepayment and extension risk.

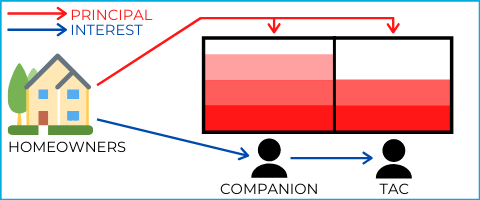

Targeted amortization class (TAC) CMOs are similar to PACs, but they use only one companion class and protect only against prepayment risk.

Here, the single (front-end) companion class absorbs principal that arrives faster than expected. That makes the TAC’s principal payments more predictable when prepayments increase.

Because there’s no back-end companion class, TACs are still exposed to extension risk. If principal arrives slower than expected, the TAC is affected much like a plain vanilla tranche.

Sometimes firms separate a plain vanilla tranche into different income streams.

Principal-only (PO) CMOs represent only the principal portion of the cash flows.

PO investors earn more when principal is returned sooner. Example:

So:

That means PO investors generally benefit from prepayments and are hurt by extension risk.

Interest-only (IO) CMOs represent only the interest portion of the cash flows.

IO investors benefit when mortgages stay outstanding longer, because that produces more interest payments.

A key twist is how IO tranches respond to interest rate changes. Most debt securities move inversely with interest rates (rates up, prices down). IO tranches behave the opposite way.

The last type of CMO to know is the Z-tranche CMO.

Like long-term zero coupon bonds, Z-tranches are typically the most volatile CMO type. When interest rates change, their values can swing significantly.

All CMOs share some common characteristics.

Complexity matters because many investors have difficulty understanding how different tranches behave under changing interest rates and prepayment patterns.

Even though complex CMOs may be unsuitable for many retail investors, they’re often AAA (or highly) rated because of the underlying collateral. Many CMOs are built from agency pass through certificates, and those agencies have direct or indirect federal backing. If homeowners stop making mortgage payments, the agencies step in and make payments on their behalf. As a result, typical agency-based CMOs are generally considered fairly low risk.

Private label CMOs are CMOs not created from federal agency pass through certificates. Instead, they’re created from mortgage inventories held by private financial firms, without government backing. That can add significant risk.

Sign up for free to take 11 quiz questions on this topic