There are many risks that bonds are subject to. We’ll group them into two categories: systematic and non-systematic.

As a reminder, systematic risks negatively affect a large portion of the market (or the entire market). For bonds, the two key systematic risks are interest rate risk and inflation (purchasing power) risk.

Earlier in this chapter, we discussed price volatility, which is closely tied to interest rate risk. Bonds with long maturities and low coupons tend to move the most in price when market conditions change. Most of the time, those price changes are driven by changes in interest rates.

Interest rate risk (sometimes called market risk for bonds) is the risk that interest rates rise, which pushes bond market prices down. When new bonds are issued at higher interest rates, older bonds with lower coupons become less attractive. Their market prices fall until their yields are competitive again. Interest rate risk applies to all fixed-income investments, including preferred stock.

Most bonds pay a fixed interest rate, but variable rate bonds do exist (we’ll cover specifics in later sections). These securities have coupons that reset periodically (often monthly or semi-annually) based on interest rate changes. Because the coupon adjusts, their market values tend to stay more stable. As a result, variable rate securities largely avoid interest rate risk.

We discussed inflation (purchasing power) risk in the preferred stock chapter. This risk occurs when inflation reduces the real value of an investment’s cash flows. Bonds are especially exposed because their coupons are typically fixed. Investors receive the same dollar amount of interest over the life of the bond, but if prices rise (for everything from groceries to housing), that fixed interest payment buys less.

When you prepared for the SIE exam, you learned how the Federal Reserve influences interest rates to manage the economy. When inflation rises, the Fed often raises interest rates to reduce overall demand (borrowing becomes more expensive). This can help stabilize prices. That’s why purchasing power risk and interest rate risk are closely connected: when interest rates rise, bond market prices fall.

Just like interest rate risk, purchasing power risk generally increases as maturity increases. A longer maturity means you’re locked into fixed payments for a longer time, giving inflation more time to erode their value. One common way investors reduce inflation risk is by using short-term bonds. When a short-term bond matures, you can reinvest the proceeds at then-current (potentially higher) interest rates instead of being stuck with a lower rate for many years.

Non-systematic risks affect specific issuers or securities rather than the entire market. Bonds have several important non-systematic risks.

Default risk (also called credit risk) is the risk that an issuer can’t make required interest and/or principal payments. The most common cause is bankruptcy.

Bankruptcy isn’t common, but it does happen. Corporations and even governments can default on their debts (though government defaults are rare). For example, the city of Detroit declared bankruptcy and defaulted on its bonds in 2013. It was (and still is) the largest municipal default in U.S. history. If you held Detroit bonds at the time, you likely lost a substantial amount of money.

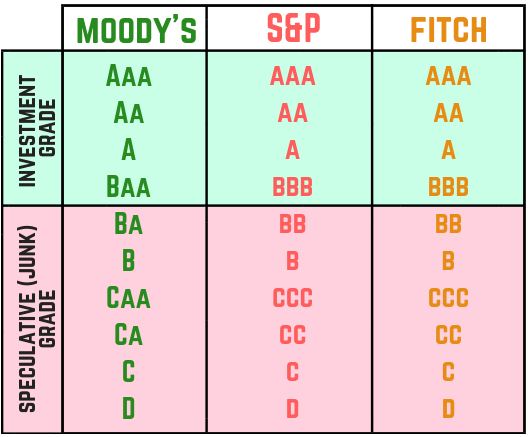

Rating agencies help investors assess a bond’s default risk. Standard & Poors (S&P), Moody’s, and Fitch are the three rating agencies to know for the exam. Their rating symbols differ slightly, but they all focus on default risk. Here’s how their ratings appear:

It’s important to distinguish between investment grade and speculative bonds:

Liquidity risk (also called marketability risk) is the risk that a security can’t be sold quickly at a fair price. In other words, you may have to accept a deep discount to sell. Some investments have higher liquidity risk than others. For example, municipal bonds are known for liquidity risk (we’ll discuss why in a future chapter).

In general, the less desirable a bond is to investors, the more liquidity risk it has. For instance, if a company is on the brink of bankruptcy, you may not be able to sell its bonds without a steep price cut (or possibly not at all).

Legislative risk is the risk that a new law or regulation (usually domestic) negatively affects an investment. For example, the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration in 2018 increased the cost of doing business with certain foreign companies. Investors holding securities tied to international trade experienced legislative risk when markets responded negatively to the trade war.

Political risk is the risk that government instability or a sudden change in government harms an investment. For example, suppose you own a Ukrainian bond. If an unexpected military coup replaces the government, the bond could default. Unless the new government chooses to honor the old government’s debts, you could lose a significant amount of money.

Political instability can happen anywhere, but it’s generally treated as a foreign risk. The United States has political disagreements, but it has a relatively stable political structure.

Reinvestment risk is the risk that you’ll have to reinvest cash flows at lower rates when interest rates fall. You could argue reinvestment risk has a systematic element, but it tends to matter most for bonds with high coupons, frequent interest payments, and callable bonds.

Even though bond prices typically rise when interest rates fall, reinvestment risk focuses on what happens to the cash you receive. Long-term investors often keep their money invested continuously. When a bond pays interest, that cash can be reinvested into new bonds (or more of the same bond). If interest rates have fallen, that reinvestment happens at lower yields.

Bonds with the largest and most frequent interest payments have the most reinvestment risk. In the U.S. government bond chapter, you’ll learn about mortgage-backed securities, which make monthly payments. Because they generate cash to reinvest so often, they have high reinvestment risk. The more cash to reinvest, the more reinvestment risk. By contrast, zero coupon bonds are considered to have no reinvestment risk. If a bond doesn’t pay ongoing interest, there’s nothing to reinvest.

Earlier in this chapter, we reviewed callable bonds. Call risk is a type of reinvestment risk. It occurs when a callable bond is likely to be called (or is called). Bonds are most likely to be called when interest rates fall, because issuers can refinance by issuing new bonds at lower rates.

Call risk is often considered the worst form of reinvestment risk. Instead of reinvesting only the interest payments at lower rates, the investor must reinvest both the interest and the principal returned when the bond is called. Because a larger amount of capital must be reinvested, call risk can be substantial.

Sign up for free to take 13 quiz questions on this topic