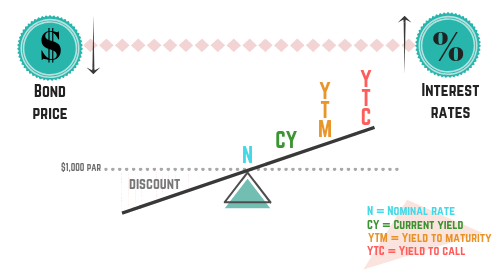

Here’s a summary of the discount bond example from the previous sections.

A 10 year, $1,000 par, 4% bond is trading at $800. The bond is callable at par after 5 years.

Coupon = 4%

Current yield = 5%

YTM = 6.7%

YTC = 8.9%

This order isn’t a coincidence. Every discount bond shows the same relationship among these yields:

You can calculate each yield, but for many exam questions you mainly need to know which yield is higher or lower. A common visual for this is the bond see-saw.

The bond see-saw is a quick way to connect a bond’s price to its yields. Many test-takers memorize it and rewrite it on scratch paper at the start of the exam so they can answer yield relationship questions without doing full calculations.

NASAA tends to emphasize yield relationships (which yield is higher or lower) more than detailed yield calculations. You may still be asked to calculate current yield, but knowing the typical order of yields is often more useful - especially for eliminating incorrect answer choices.

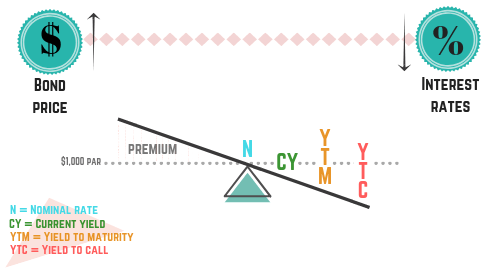

Now let’s use the premium bond example from the previous sections.

A 10 year, $1,000 par, 4% bond is trading at $1,100. The bond is callable at par after 5 years.

Coupon = 4%

Current yield = 3.6%

YTM = 2.9%

YTC = 1.9%

Again, this order follows a consistent pattern. Every premium bond shows the same relationship among these yields:

You can calculate each yield, or you can use the bond see-saw.

For premium bonds, the price side points upward because the bond is trading above par. Keep the yield order on the see-saw in mind, and yield-based questions become much more straightforward.

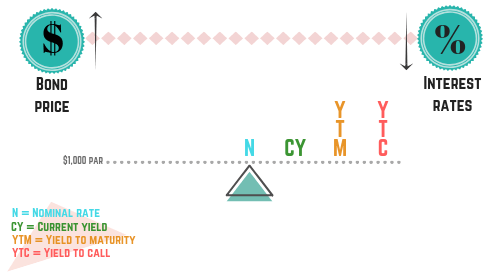

We’ve seen how price affects yields for bonds purchased at a discount and at a premium. What happens if a bond is purchased at par ($1,000)?

When a bond is purchased at par, all yields equal the coupon.

The investor isn’t gaining or losing anything from the purchase price:

So the only return comes from the coupon payments. For a bond purchased at par, the see-saw looks like this:

Here, the coupon lines up with current yield, YTM, and YTC. If you see a question about par bond yields, keep it simple: they’re all the same.

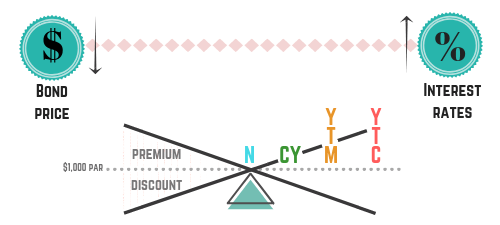

Yield is a major topic on the Series 7 exam. The bond see-saw helps you visualize the relationship between:

We’ve looked at the see-saw for discount, premium, and par bonds. Here they are together:

If you use a “dump sheet,” the bond see-saw is often worth including. A dump sheet is a set of key visuals or reminders you write on scratch paper after the exam begins. Many test-takers memorize visuals like the bond see-saw and rely on them for yield questions.

Some also use acronyms, like this:

CYM Call

CY = Current Yield

M = yield to Maturity

Call = yield to Call

Use whatever memory aid helps you recall the terms and their order.

Two yields are typically provided when a bond quote is given to investors (and also disclosed on trade confirmations):

Yield to worst is meant to show a “worst-case scenario” based on the bond being held to maturity or being called at the earliest possible date.

If a callable bond is bought at a discount, the investor is provided the YTM. An investor would earn a higher annualized return if a discount bond is redeemed sooner because the discount is earned faster. For example, assume a 20 year bond that is callable in 10 years at par is purchased for 90 ($900). The investor would earn the $100 discount faster if the bond is called before maturity, resulting in a higher annualized return. The YTM assumes the discount bond is held to maturity, which reflects the discount being gained more slowly and the lowest possible yield (unless the bond defaults).

If a callable bond is bought at a premium, the investor is provided the YTC. An investor would earn a higher annualized return if a premium bond is held to maturity because the premium is lost more slowly. For example, assume a 20 year bond that is callable in 10 years at par is purchased for 110 ($1,100). The investor would lose the $100 premium more slowly if the bond is held to maturity, resulting in a higher annualized return. The YTC assumes the premium bond is called at the first possible date, which reflects the premium being lost faster and the lowest possible yield (unless the bond defaults).

No YTC exists if a bond is not callable. Therefore, the YTM is always provided when quoting a non-callable bond.

Assuming a bond is callable, here’s the “yield to worst” summary:

Sign up for free to take 10 quiz questions on this topic