Long straddles

When you can’t confidently predict whether the market will go up or down, but you do expect volatility, a long straddle can make sense. This strategy can profit if the stock price moves significantly in either direction.

These are the components of a long straddle:

Long call & long put*

*Must be the same strike price and expiration

For example:

Long 1 ABC Jan 60 call

Long 1 ABC Jan 60 put

As you already know, a long call contract provides the “right to buy,” while a long put contract provides the “right to sell.” The long call is bullish (it benefits from rising prices). The long put is bearish (it benefits from falling prices). By buying both, the investor is betting on market volatility rather than direction.

-

If the stock’s market price rises above the call’s strike price (“call up”), the investor can exercise the call and potentially profit. The stock would be purchased at the strike price and sold at the higher market price. The investor profits if that gain is greater than the combined premiums paid for both options.

-

If the stock’s market price falls below the put’s strike price (“put down”), the investor can exercise the put and potentially profit. The stock would be purchased at the lower market price and sold at the higher strike price. Again, the investor profits only if the gain is greater than the combined premiums.

A long straddle can profit in either a bull or bear market, but it has an important cost: you pay two premiums. That means the winning option must gain enough intrinsic value to cover both premiums. If the stock stays near the shared strike price, the investor can lose most or all of the combined premiums.

Let’s walk through several scenarios using the same long straddle:

An investor goes long 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and long 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price rises to $100?

Can you figure it out?

Answer = $3,100 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$400 |

| Buy put | -$500 |

| Exercise call - buy shares | -$6,000 |

| Sell shares | +$10,000 |

| Total | +$3,100 |

At $100, the call is “in the money” (it has intrinsic value), and the put is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value). The put expires worthless, and the call is exercised, allowing the investor to buy ABC at $60 and sell at $100.

- Intrinsic value on the call = $100 − $60 = $40 per share = $4,000

- Combined premiums paid = $4 + $5 = $9 per share = $900

- Net gain = $4,000 − $900 = $3,100

Only one option finished in the money, but the move was large enough that the call’s intrinsic value more than covered the combined premium.

The maximum gain for a long straddle is unlimited*. The further the market rises, the more intrinsic value the call option gains.

What happens if the market rises by a small amount?

An investor goes long 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and long 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price rises to $69?

Answer = $0 (breakeven)

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$400 |

| Buy put | -$500 |

| Exercise call - buy shares | -$6,000 |

| Sell shares | +$6,900 |

| Total | $0 |

At $69, the call is in the money and the put is out of the money. The call’s intrinsic value is $69 − $60 = $9 per share ($900 total), which exactly offsets the $900 combined premium.

This is the upside breakeven. For a long straddle, you can always find it by:

- Upside breakeven = strike price + combined premiums

In this example: $60 + $9 = $69.

Let’s try another example:

What happens if the market rises by a small amount?

An investor goes long 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and long 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price rises to $62?

Answer = $700 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$400 |

| Buy put | -$500 |

| Exercise call - buy shares | -$6,000 |

| Sell shares | +$6,200 |

| Total | -$700 |

At $62, the call has $2 of intrinsic value ($200 total), but the combined premium was $900. The net result is a $700 loss.

This is the key risk of a long straddle: not enough movement. The closer the stock stays to the shared strike price, the more likely the investor is to lose some or all of the combined premiums.

What happens if the market remains flat?

An investor goes long 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and long 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price stays at $60?

Answer = $900 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$400 |

| Buy put | -$500 |

| Total | -$900 |

At $60, both options are “at the money,” so neither has intrinsic value. Both expire worthless, and the investor loses the combined premiums ($900).

This is the maximum loss for the long straddle.

To find the maximum loss for any long straddle, you can use this formula:

What happens if the market falls a small amount?

An investor goes long 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and long 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price falls to $57?

Answer = $600 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$400 |

| Buy put | -$500 |

| Buy shares | -$5,700 |

| Exercise put - sell shares | +$6,000 |

| Total | -$600 |

At $57, the put is in the money by $3 ($300 total). That $300 intrinsic value doesn’t cover the $900 combined premium, so the investor still has a $600 loss.

Again, limited price movement is the enemy of a long straddle.

What happens if the market falls a little further?

An investor goes long 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and long 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price falls to $51?

Answer = $0 (breakeven)

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$400 |

| Buy put | -$500 |

| Buy shares | -$5,100 |

| Exercise put - sell shares | +$6,000 |

| Total | $0 |

At $51, the put has $9 of intrinsic value ($900 total), which exactly offsets the $900 combined premium.

This is the downside breakeven. For a long straddle, you can always find it by:

- Downside breakeven = strike price − combined premiums

In this example: $60 − $9 = $51.

Here’s the general formula for breakeven on straddles:

You’ll learn more about this in the next section, but the breakeven formula is the same for both long and short straddles.

Straddles are one of the only options strategies with multiple breakevens. To find both quickly:

- Add up the combined premiums.

- Add the combined premiums to the strike price (upside breakeven).

- Subtract the combined premiums from the strike price (downside breakeven).

In this example, the two breakevens are $51 and $69.

What happens if the market falls significantly?

An investor goes long 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and long 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price falls to $25?

Answer = $2,600 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$400 |

| Buy put | -$500 |

| Buy shares | -$2,500 |

| Exercise put - sell shares | +$6,000 |

| Total | +$2,600 |

At $25, the put is in the money by $35 ($3,500 total). After subtracting the $900 combined premium, the net gain is $2,600.

Only one option finished in the money, but the move was large enough that the put’s intrinsic value more than covered the combined premium.

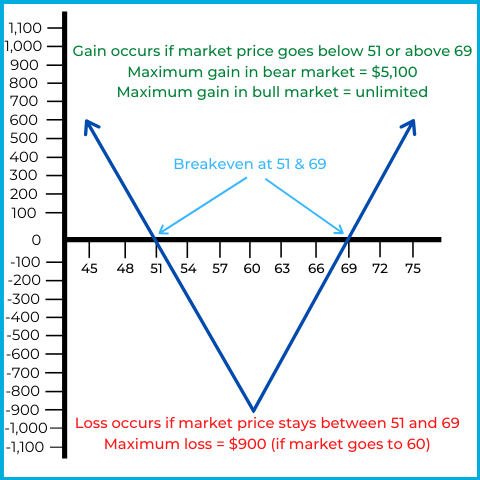

Let’s look at the options payoff chart to summarize the big picture for this long straddle. First, here’s the position again:

Long 1 ABC Jan 60 call @ $4

Long 1 ABC Jan 60 put @ $5

Here’s the payoff chart:

The horizontal axis represents the market price of ABC stock, while the vertical axis represents overall gain or loss.

The chart shows the key idea:

- The maximum loss occurs at the strike price ($60) and equals the combined premiums ($900).

- Above $60, the call gains intrinsic value; below $60, the put gains intrinsic value.

- The breakevens are $69 on the upside and $51 on the downside.

If the market price rises above $69, the position becomes profitable and has unlimited upside potential. If the market price falls below $51, the position becomes profitable on the downside, with gain potential up to $5,100 (which would occur if the stock fell to $0).

In the last few examples, we’ll look at what happens when the investor closes out the contracts at intrinsic value. Closing out means trading the contracts (selling them) instead of exercising them or letting them expire.

An investor goes long 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and long 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. ABC’s market falls to $45 and the investor closes the contracts at intrinsic value. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $600 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$400 |

| Buy put | -$500 |

| Close call | $0 |

| Close put | +$1,500 |

| Total | +$600 |

At $45, the put has $15 of intrinsic value and the call has $0. The investor closes both positions by selling the options:

- Total paid in premiums = $9 per share ($900)

- Total received when closing = $15 per share ($1,500)

- Net gain = $1,500 − $900 = $600

As a reminder, closing transactions reverse the opening transactions. Since the investor opened the straddle with two purchases, they close it with two sales.

Let’s examine one more scenario involving closing transactions:

An investor goes long 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and long 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. ABC’s market rises to $66 and the investor closes the contracts at intrinsic value. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $300 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$400 |

| Buy put | -$500 |

| Close call | +$600 |

| Close put | $0 |

| Total | -$300 |

At $66, the call has $6 of intrinsic value and the put has $0. The investor closes both positions by selling the options:

- Total paid in premiums = $9 per share ($900)

- Total received when closing = $6 per share ($600)

- Net loss = $600 − $900 = −$300

As in the prior example, the investor closes the straddle with two sales because the straddle was opened with two purchases.

This video covers the important concepts related to long straddles:

For suitability, long straddles should only be recommended to aggressive options traders if volatility is expected. Although the maximum loss is limited to the premiums, losses can add up quickly due to the short-term nature of options. The investor realizes a loss if volatility does not materialize before expiration (9 months or less for standard options).