Short straddles are essentially the opposite of long straddles. In the previous chapter, we learned that long straddles can profit when the market is volatile. Conversely, short straddles can profit when the market is flat (neutral).

These are the components of a short straddle:

Short call & short put*

*Must be the same strike price and expiration

For example:

Short 1 ABC Jan 60 call

Short 1 ABC Jan 60 put

A short call creates an obligation to sell shares at the strike price if assigned. A short put creates an obligation to buy shares at the strike price if assigned.

By selling both options, the investor is betting on market neutrality (little to no price movement).

If the stock’s market price stays flat, both options may expire worthless. That happens when ABC’s market price is exactly the shared strike price at expiration, which is the best-case scenario for a short straddle.

If the stock’s market price rises, the call will be assigned (exercised). This is the most dangerous direction because the short call obligates the investor to sell shares at the strike price. If the investor doesn’t already own the shares, they must buy them at the higher market price and then sell at the lower strike price. The higher the market price rises, the larger the loss.

If the stock’s market price falls, the put will be assigned (exercised). This also creates significant risk because the short put obligates the investor to buy shares at the strike price even though the market price is lower. The further the market price falls, the more the investor overpays, and the larger the loss.

A short straddle is risky because it involves two naked (uncovered) options. However, the investor receives two premiums up front. Losses must exceed the combined premiums before the investor has an overall loss. In other words, the investor is most likely to profit when the stock’s market price doesn’t move dramatically.

Let’s walk through several scenarios to see how a short straddle behaves:

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market rises to $120?

Can you figure it out?

Answer = $5,100 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Buy shares | -$12,000 |

| Call assigned - sell shares | +$6,000 |

| Total | -$5,100 |

At $120, the call is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the put is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value). The put expires worthless, but the call is assigned (exercised), requiring the investor to fulfill the obligation to sell.

The investor buys the stock in the market at $120 and then sells at $60, creating a $60 loss per share, or $6,000 total ($60 x 100 shares). The $900 combined premium received up front reduces the loss to $5,100.

The investor wanted a flat market and got the opposite. Even though only one option went in the money, the short call produced a large loss. The premiums offset the loss slightly, but the overall result is still substantial.

The maximum loss for a short straddle is unlimited. The further the market rises, the larger the loss because of the short naked call.

What happens if the market rises a moderate amount?

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price rises to $69?

Answer = $0 (breakeven)

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Buy shares | -$6,900 |

| Call assigned - sell shares | +$6,000 |

| Total | $0 |

At $69, the call is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the put is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value). The put expires worthless, but the call is assigned (exercised).

The investor buys the stock at $69 and sells at $60, creating a $9 loss per share, or $900 total ($9 x 100 shares). The $900 combined premium received up front offsets the loss, resulting in breakeven.

$69 is one of two breakevens for this example (we’ll find the other one later). On the upside, the straddle breaks even when the loss on the short call equals the combined premiums. That’s why the upside breakeven is:

What happens if the market rises slightly?

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price rises to $64?

Answer = $500 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Buy shares | -$6,400 |

| Call assigned - sell shares | +$6,000 |

| Total | +$500 |

At $64, the call is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the put is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value). The put expires worthless, but the call is assigned (exercised).

The investor buys the stock at $64 and sells at $60, creating a $4 loss per share, or $400 total ($4 x 100 shares). The $900 combined premium received up front more than offsets that loss, leaving a $500 gain.

A short straddle works best when the stock stays close to the shared strike price. Small moves can still be profitable because the premiums provide a cushion.

What happens if the market remains flat?

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price stays at $60?

Answer = $900 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Total | +$900 |

At $60, both options are “at the money” and expire worthless (contracts must have intrinsic value to be exercised). The investor keeps the entire $900 in combined premiums.

This is the best-case scenario and produces the maximum gain.

The maximum gain for a short put can be found by using this formula:

What happens if the market falls a small amount?

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price falls to $59?

Answer = $800 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Put assigned - buy shares | -$6,000 |

| Share value | +$5,900 |

| Total | +$800 |

At $59, the put is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the call is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value). The call expires worthless, but the put is assigned (exercised).

The investor buys shares for $60 that are worth $59, creating a $1 loss per share, or $100 total ($1 x 100 shares). The $900 combined premium received up front offsets the loss, resulting in an $800 gain.

Again, the closer the stock stays to the shared strike price, the more likely the investor profits.

What happens if the market falls a little further?

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price falls to $51?

Answer = $0 (breakeven)

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Put assigned - buy shares | -$6,000 |

| Share value | +$5,100 |

| Total | $0 |

At $51, the put is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the call is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value). The call expires worthless, but the put is assigned (exercised).

The investor buys shares for $60 that are worth $51, creating a $9 loss per share, or $900 total ($9 x 100 shares). The $900 combined premium received up front offsets the loss, resulting in breakeven.

$51 is the other breakeven for this example. On the downside, the straddle breaks even when the loss on the short put equals the combined premiums. That’s why the downside breakeven is:

Here’s the general formula for breakeven on straddles:

The breakeven formula is the same for both long and short straddles.

Straddles are one of the only options strategies with multiple breakevens. To find both quickly:

In summary, the two breakevens for this long straddle are $51 and $69.

What happens if the market falls significantly?

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. What is the gain or loss if ABC’s market price falls to $25?

Answer = $2,600 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Put assigned - buy shares | -$6,000 |

| Share value | +$2,500 |

| Total | -$2,600 |

At $25, the put is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the call is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value). The call expires worthless, but the put is assigned (exercised).

The investor buys shares for $60 that are worth $25, creating a $35 loss per share, or $3,500 total ($35 x 100 shares). The $900 combined premium received up front reduces the loss to $2,600.

The investor wanted a flat market and got a large downward move. Even though only one option went in the money, the short put produced a large loss. The premiums offset the loss slightly, but the overall result is still substantial.

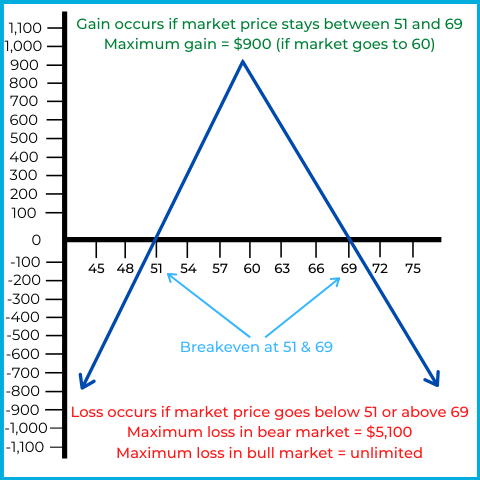

Let’s look at the options payoff chart to summarize the big picture of this short straddle. First, here’s the example again:

Short 1 ABC Jan 60 call @ $4

Short 1 ABC Jan 60 put @ $5

Here’s the payoff chart:

The horizontal axis represents the market price of ABC stock, while the vertical axis represents overall gain or loss.

As the payoff chart shows, the investor reaches the maximum gain of $900 when the market price is $60. At that point, both options expire worthless, and the combined premiums are the profit.

If the market price rises above or falls below $60, the call or the put goes “in the money” and gains intrinsic value. Remember: option writers (sellers) lose when their contracts gain intrinsic value. Intrinsic value benefits the holder (buyer, long side) and hurts the writer (seller, short side).

Any market price below $51 results in a loss as the investor is eligible for up to $5,100 of liability (a $5,100 loss would occur if the market price falls to $0).

In the last few examples, we’ll look at what happens when the investor closes out the contracts at intrinsic value. As we’ve learned previously, closing out contracts means trading the contracts instead of waiting for assignment or expiration.

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. ABC’s market price falls to $40 and the investor closes the contracts at intrinsic value. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $1,100 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Close call | $0 |

| Close put | -$2,000 |

| Total | -$1,100 |

At $40, the put is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the call is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value).

The investor received $9 in total premium up front but pays $20 to close the put. That difference is an $11 loss per share, or $1,100 total ($11 x 100 shares).

Closing out means doing the opposite of the opening transaction. Since both options were sold to open the short straddle (opening sales), both must be bought to close (closing purchases). After selling $900 of options and buying to close for $2,000, the investor has a $1,100 loss.

Let’s examine one more closing-transaction scenario:

An investor goes short 1 ABC Jan 60 call at $4 and short 1 ABC Jan 60 put at $5 when ABC’s market price is $60. ABC’s market price rises to $67 and the investor closes the contracts at intrinsic value. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $200 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell call | +$400 |

| Sell put | +$500 |

| Close call | -$700 |

| Close put | $0 |

| Total | +$200 |

At $67, the call is “in the money” (has intrinsic value) and the put is “out of the money” (no intrinsic value).

The investor received $9 in total premium up front and pays $7 to close the call. That difference is a $2 gain per share, or $200 total ($2 x 100 shares).

As before, both options were sold to open (opening sales), so both must be bought to close (closing purchases). After selling $900 of options and buying to close for $700, the investor has a $200 gain.

This video covers the important concepts related to short straddles:

For suitability, short straddles should only be recommended to aggressive options traders with a substantial net worth when a flat market is expected. If there is unexpected volatility, the investor is subject to unlimited risk. The fewer assets or money an investor has, the less likely they should be selling straddles.

Sign up for free to take 6 quiz questions on this topic