Accretion & amortization

Bonds pay interest, and for most bonds that interest is taxable in some way (municipal bond interest is the main exception). When you buy a bond at a discount or a premium, there can also be tax effects beyond the coupon interest.

This section explains:

- How discounts are handled through accretion

- How premiums are handled through amortization

Accretion

Accretion means treating a bond’s discount as additional interest income over time. In other words, you pay tax on part of the discount each year (instead of waiting until maturity).

Let’s use an example:

An investor purchases a 5-year, $1,000 par, 6% corporate bond for 95.

Here’s what that price means:

- Par value = $1,000

- Purchase price = 95% of par = $950

- Discount = $1,000 − $950 = $50

- Time to maturity = 5 years

- Annualized discount = $50 / 5 = $10 per year

The bond pays $60 of coupon interest each year (6% × $1,000). If the investor accretes the discount, the IRS treats the $10 per year discount as additional interest income.

If the bond is accreted and held to maturity, the taxable interest each year looks like this:

| Year | Taxable interest | Accreted discount | Total taxable interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $60 | $10 | $70 |

| 2 | $60 | $10 | $70 |

| 3 | $60 | $10 | $70 |

| 4 | $60 | $10 | $70 |

| 5 | $60 | $10 | $70 |

When an investor accretes a discount bond, they pay taxes on the discount annually.

In some circumstances, investors can choose whether to accrete. If an investor does not accrete a discount bond, they wait until the bond matures (or is sold) to recognize the discount for tax purposes. In that case, the taxable interest looks like this:

| Year | Taxable interest | Non-accreted discount | Total taxable interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $60 | $0 | $60 |

| 2 | $60 | $0 | $60 |

| 3 | $60 | $0 | $60 |

| 4 | $60 | $0 | $60 |

| 5 | $60 | $50 | $110 |

If the investor chooses not to accrete, the total taxable amount over the life of the bond is the same - the difference is timing. Here, the investor reports $60 of taxable interest for four years, then $110 in the final year.

Regardless of whether the discount is accreted for tax reporting, the bond’s cost basis increases each year by the annualized discount amount. If the bond is held to maturity, there is no capital gain or loss. The discount is treated as interest income, not a capital gain.

A capital gain or loss can occur only if the bond is sold before maturity. Here’s an example:

An investor purchases a 5-year, $1,000 par, 6% corporate bond for 95. At the end of 3 years, the investor sells the bond at 96. If they choose to accrete the bond, what are the tax consequences that year?

First, here’s the result:

- Taxable interest income = $70

- Reported gain/loss = $20 capital loss

Because the investor accretes the bond, taxable interest for the year includes:

- Coupon interest: $60

- Accreted discount: $10

So taxable interest income is $70.

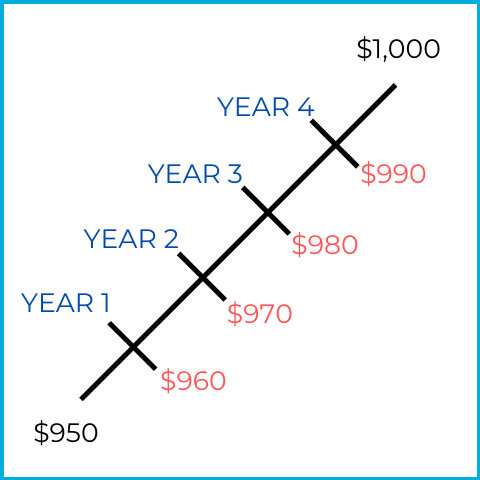

Now look at the capital loss. The key is that the cost basis rises by $10 each year:

After 3 years:

- Original cost basis: $950

- Plus accretion: $10 × 3 = $30

- Adjusted cost basis: $980

Sales proceeds are 96% of par = $960. Since $960 − $980 = −$20, the investor reports a $20 capital loss.

Next, try one on your own:

An investor purchases $1,000 par, 4% debenture with 8 years to maturity at 96. At the end of 5 years, the investor sells the bond at 99. If they do not accrete the bond, what are the tax consequences that year?

- Taxable interest income = $65

- Reported gain/loss = $5 capital gain

Because the investor did not accrete the bond annually, they recognize the discount as interest income when the bond is sold.

Step by step:

- Coupon interest each year = 4% × $1,000 = $40

- Total discount = $1,000 − $960 = $40

- Annualized discount = $40 / 8 = $5 per year

- Years held = 5

- Discount recognized as interest at sale = $5 × 5 = $25

So in the year of sale, taxable interest income is:

- $40 coupon interest

-

- $25 discount treated as interest

- = $65 total taxable interest

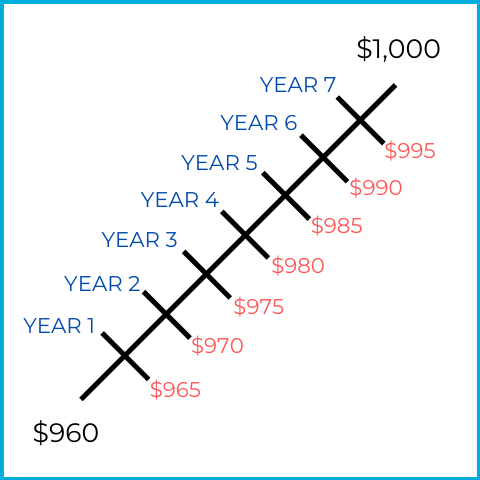

Now for the capital gain: the cost basis still increases by $5 per year.

After 5 years:

- Original cost basis: $960

- Plus basis increase: $5 × 5 = $25

- Adjusted cost basis: $985

Sales proceeds are 99% of par = $990. Since $990 − $985 = $5, the investor reports a $5 capital gain.

Amortization

Amortization means spreading a bond’s premium over time to reduce taxable interest each year. You’re effectively treating part of the coupon interest as a return of the premium you paid.

Example:

An investor purchases a 5-year, $1,000 par, 6% corporate bond for 105.

What the price implies:

- Par value = $1,000

- Purchase price = 105% of par = $1,050

- Premium = $1,050 − $1,000 = $50

- Time to maturity = 5 years

- Annualized premium = $50 / 5 = $10 per year

The bond pays $60 of coupon interest each year. If the investor amortizes the premium, they reduce taxable interest by $10 per year.

If the bond is amortized and held to maturity, taxable interest looks like this:

| Year | Taxable interest | Amortized premium | Total taxable interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $60 | $10 | $50 |

| 2 | $60 | $10 | $50 |

| 3 | $60 | $10 | $50 |

| 4 | $60 | $10 | $50 |

| 5 | $60 | $10 | $50 |

When an investor amortizes a premium bond, they reduce taxable interest annually.

In some circumstances, investors can choose whether to amortize. If an investor does not amortize a premium bond, they wait until maturity (or sale) to apply the premium against interest income. In that case, taxable interest looks like this:

| Year | Taxable interest | Non-amortized premium | Total taxable interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $60 | $0 | $60 |

| 2 | $60 | $0 | $60 |

| 3 | $60 | $0 | $60 |

| 4 | $60 | $0 | $60 |

| 5 | $60 | $50 | $10 |

If the investor chooses not to amortize, the total adjustment is the same - the difference is when it shows up. Here, the investor reports $60 of taxable interest for four years, then only $10 in the final year.

Regardless of whether the premium is amortized for tax reporting, the bond’s cost basis decreases each year by the annualized premium amount. Remember, if the bond is held to maturity, there is no capital gain or loss. The premium is handled through interest income, not capital loss.

A capital gain or loss can occur only if the bond is sold before maturity. Example:

An investor purchases a $1,000 par, 7% Treasury bond with 4 years to maturity at 108. At the end of 2 years, the investor sells the bond at 101. If they amortize the bond, what are the tax consequences that year?

Can you figure it out?

- Taxable interest income = $50

- Reported gain/loss = $30 capital loss

Because the investor amortizes the bond:

- Coupon interest = 7% × $1,000 = $70

- Premium = $1,080 − $1,000 = $80

- Annualized premium = $80 / 4 = $20 per year

Taxable interest income for the year is:

- $70 coupon interest

- − $20 amortized premium

- = $50 taxable interest

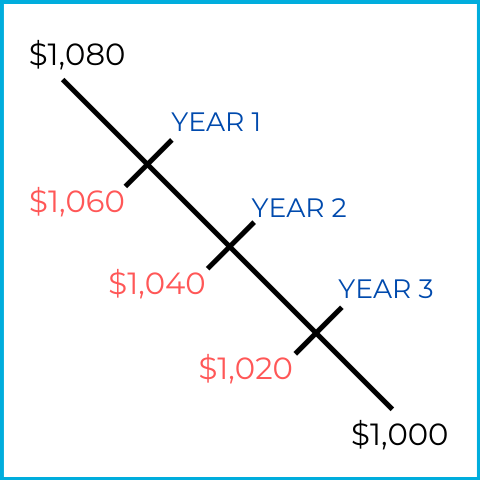

For the capital loss, the cost basis falls by $20 each year:

After 2 years:

- Original cost basis: $1,080

- Minus basis reduction: $20 × 2 = $40

- Adjusted cost basis: $1,040

Sales proceeds are 101% of par = $1,010. Since $1,010 − $1,040 = −$30, the investor reports a $30 capital loss.

Let’s try one last example:

An investor purchases a $1,000 par, 13% mortgage bond with 5 years to maturity at 115. At the end of 4 years, the investor sells the bond at 107. If they do not amortize the bond, what are the tax consequences that year?

- Taxable interest income = $10

- Reported gain/loss = $40 capital gain

Because the investor did not amortize annually, they apply the premium against interest income when the bond is sold.

Step by step:

- Coupon interest each year = 13% × $1,000 = $130

- Premium = $1,150 − $1,000 = $150

- Annualized premium = $150 / 5 = $30 per year

- Years held = 4

- Premium applied against interest at sale = $30 × 4 = $120

So taxable interest income in the year of sale is:

- $130 coupon interest

- − $120 premium adjustment

- = $10 taxable interest

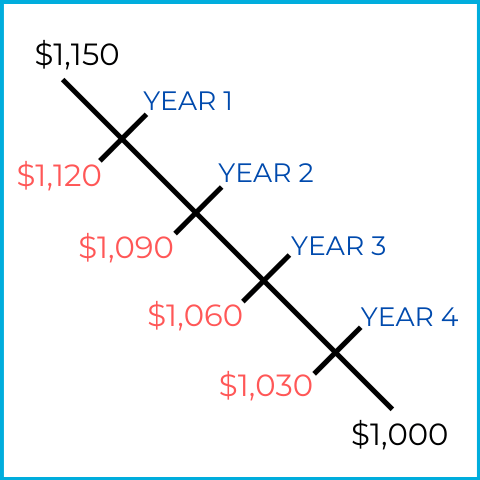

For the capital gain, the cost basis still falls by $30 per year:

After 4 years:

- Original cost basis: $1,150

- Minus basis reduction: $30 × 4 = $120

- Adjusted cost basis: $1,030

Sales proceeds are 107% of par = $1,070. Since $1,070 − $1,030 = $40, the investor reports a $40 capital gain.

Choosing to accrete or amortize

You’ve seen two ways to handle discounts and premiums:

- Accrete/amortize annually, which spreads the tax effect over time

- Wait until maturity or sale, which concentrates the tax effect later

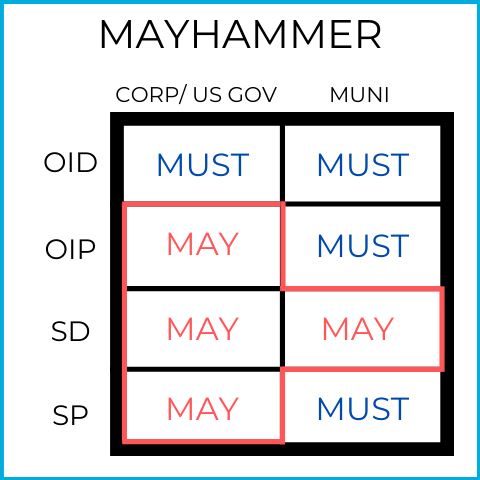

Sometimes the investor can choose, and sometimes the IRS requires a specific treatment. This visual summarizes the rules you need to know:

- OID = original issue discount

- OIP = original issue premium

- SD = secondary market discount

- SP = secondary market premium

The “mayhammer” is a useful exam memory tool. The red hammer highlights the situations where the investor may choose whether to accrete/amortize.

In the other situations, the investor must accrete or amortize, meaning the discount or premium must be reflected in annual taxes.

A typical exam question might look like this:

Which of the following statements are false?

A) New issue corporate bonds sold at a discount must be accreted

B) New issue municipal bonds sold at a discount must be accreted

C) New issue corporate bonds sold at a premium must be amortized

D) New issue municipal bonds sold at a premium must be amortized

Do you know the answer?

Answer = C

Using the “mayhammer,” you’ll find that A, B, and D are true: those situations require annual accretion or amortization.

A new issue corporate bond sold at a premium (OIP) is a “may,” meaning the investor can either:

- amortize the premium annually, or

- wait until the end of the bond to take the full adjustment.

Municipal bond rules

Municipal bonds are often described as “tax-free,” but they don’t avoid taxes in every situation. Two common taxable situations are:

When a municipal bond is purchased in the secondary market at a discount, the discount is fully taxable. The interest is tax-free (if a residency exists or territory bond), but the discount is taxable the same way we discussed earlier. This does not apply to new issue municipal bonds bought at a discount (that discount is tax-free).

If a municipal bond is sold prior to maturity at a gain, a tax liability can occur. Municipal bonds accrete and amortize the same way as the other bonds discussed above. If there’s a capital gain at the sale, it’s fully taxable. If there’s a capital loss at the sale, it’s potentially deductible (like any other capital loss).

When a municipal bond is purchased at a premium, the amortized premium is not deductible against municipal bond interest. The idea is simple: municipal bond interest is generally tax-free, so there’s no taxable interest to reduce. Keep in mind this is different from a capital loss, which is deductible against earned income.