Suitability

Fixed income debt securities come in many shapes and forms. While you’ll learn about corporate, municipal, and US government debt securities in future units, this section focuses on the general benefits, risks, and typical investors for bonds.

Benefits

The primary benefit of bonds is interest income. Most bonds pay interest semiannually, and those interest payments are legal obligations of the issuer. Unlike stock dividends, interest payments don’t require approval by a Board of Directors (BOD). If an issuer misses an interest or principal payment, bondholders can take legal action, including forcing the issuer into bankruptcy proceedings. Because of this, bond income is generally more predictable than stock dividends.

Capital appreciation can occur, especially if interest rates fall. However, interest rate movements aren’t easy to predict, and bonds mature at par. If you hold a bond to maturity, you’ll receive the face (par) value back at maturity. For that reason, most bond investors aren’t primarily seeking capital appreciation unless their bond is convertible*.

*We will discuss convertible bonds in the corporate debt unit. They are very similar to convertible preferred stock.

While it’s not always the case, bond market prices are often less volatile than stock prices. Since bond interest is a legal obligation and isn’t contingent on the issuer’s profitability, price fluctuations are typically milder. There are important exceptions, though. If interest rates move sharply or if the issuer is close to bankruptcy, bond prices can swing dramatically.

Some benefits depend on the issuer type:

- US Government securities are considered among the safest securities in the world, especially since the government can create its own currency to repay its debts.

- Municipal securities typically provide tax-free income if purchased by a resident.

- Corporate bonds offer a wide range of choices, from large, well-established companies to small start-ups.

Systematic risks

As a reminder, systematic risks affect a large portion of the market (or the entire market). For bonds, the two key systematic risks are interest rate risk and inflation (purchasing power) risk.

Earlier in this chapter, you learned about price volatility and duration, both of which relate to interest rate risk. Bonds with long maturities and low coupons tend to move the most in price when market conditions change. In practice, bond prices are most commonly influenced by changes in interest rates.

Interest rate risk (sometimes called market risk for bonds) is the risk that interest rates rise, which pushes bond market prices down. Prices fall because older bonds with lower coupons must become cheaper to compete with newly issued bonds offering higher interest rates. Interest rate risk applies to all fixed income investments, including preferred stock.

You also saw inflation (purchasing power) risk in the preferred stock suitability chapter. This risk occurs when inflation reduces the real value of an investment’s cash flows. Bonds are especially exposed because their coupons are fixed: investors receive a fixed dollar amount of interest over the life of the bond. If prices rise across the economy (milk, cars, real estate, and so on), that fixed interest payment buys less.

When inflation rises, the Federal Reserve (the central bank of the US) often raises interest rates to reduce overall demand (borrowing becomes more expensive). This typically helps stabilize prices of goods and services. That’s why purchasing power risk and interest rate risk are closely connected: when interest rates rise, bond market prices fall.

Just like interest rate risk, purchasing power risk increases with maturity. The longer the maturity, the more exposed the bond is to inflation over time. One common way to reduce inflation exposure is to use shorter-term bonds. When a short-term bond matures, you can reinvest the proceeds at then-current interest rates rather than being locked into a lower rate for a long period.

Non-systematic risks

Non-systematic risks affect specific issuers or securities rather than the entire market. Bonds have several important non-systematic risks.

Default risk (also called credit risk) is the risk that an issuer can’t make required interest and/or principal payments. The most common cause of default is bankruptcy.

Bankruptcy isn’t common, but it does happen. Corporations - and sometimes governments - default on their debts (government defaults are rare). For example, the city of Detroit declared bankruptcy and defaulted on their bonds in 2013. It was (and still is) the largest default by a municipal (local government) issuer in US history. If you held a Detroit bond at the time, you likely lost a substantial amount of money.

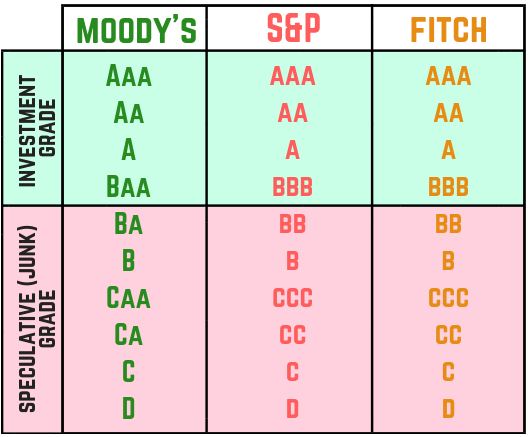

Ratings agencies help investors evaluate default risk. Standard & Poors (S&P), Moody’s, and Fitch are the three ratings agencies to know for the exam. Their rating symbols differ slightly, but all focus on default risk. Here’s how their ratings appear:

It’s important to distinguish between investment grade and speculative bonds:

- Investment grade bonds have little to no default risk. Investment grade bonds have ratings of BBB (Baa for Moody’s) or higher.

- Speculative bonds (also called junk bonds) have considerable default risk. The lower the rating, the higher the default risk. Speculative grade bonds have ratings of BB (Ba for Moody’s) or lower.

Liquidity risk (also called marketability risk) is the risk that a security can’t be sold quickly at a fair price, or that it can only be sold with a deep discount. In general, the less desirable a bond is to investors, the more liquidity risk it has. For example, if a company is close to bankruptcy, you may not be able to sell its bonds without a steep price cut (or possibly at all).

Some investments tend to have higher liquidity risk. Municipal bonds are known for liquidity risk, largely because of their tax status. Since residents may receive tax-free income, investors often trade these bonds primarily with others in the same state or locality. The smaller the municipality, the fewer potential buyers. By contrast, US Government securities trade globally and are among the most liquid investments in the world.

Legislative risk is the risk that a new law or regulation (usually domestic) negatively affects an investment. For example, the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration starting in 2018 increased the cost of doing business with foreign companies from certain countries. Investors holding securities tied to international trade experienced legislative risk when the financial markets responded negatively to the trade war.

Political risk is the risk that government instability or a sudden change in government harms an investment. For example, suppose you own a Ukrainian bond. If an unexpected military coup replaces the government, your bond could default. Unless the new government chooses to honor the old government’s debts, you could lose a significant amount of money.

Political instability can happen anywhere, but it’s generally treated as a foreign risk. The United States has political disagreements, but it has a relatively stable political structure.

Reinvestment risk is the risk that you’ll have to reinvest cash flows at lower rates when interest rates fall. While you could argue reinvestment risk has a systematic element, it tends to matter most for bonds with high coupons, frequent interest payments, and callable features.

Bond prices generally rise when interest rates fall, but reinvestment risk focuses on what happens to the cash you receive and then put back into the market. Long-term investors often keep their money invested continuously. When a bond pays interest, that cash can be used to buy another security (or more of the same security). If interest rates have fallen, that reinvested money typically earns a lower return.

Earlier in this chapter, you reviewed callable bonds. Call risk is a type of reinvestment risk that occurs when a callable bond is likely to be called (or is called). Bonds are most likely to be called when interest rates fall, allowing issuers to refinance by issuing new bonds at lower rates.

Call risk is often considered the worst form of reinvestment risk. Instead of reinvesting only the interest payments at lower rates, you must reinvest both the interest and the principal returned when the bond is called. Because a larger amount of capital is affected, call risk can be substantial.

The last risk relates to yield. Municipal bonds can provide tax-free income, but that benefit comes with a trade-off: lower yields. Issuers can offer lower yields because investors don’t pay taxes on the interest. While this isn’t always the most severe risk, an investor in a low tax bracket should generally avoid municipal investments. Otherwise, they may face opportunity cost if other investments could provide a higher after-tax return.

Typical investor

Bonds vary widely in their risks and benefits. This section describes the typical bond investor in general terms.

Compared with stocks, bonds are often preferred by older, more conservative investors. Because interest payments are legally required, bonds typically involve less risk than common stock, which usually means lower returns. Investors who want safer, more predictable income often choose debt securities over equity (stock) securities.

Remember the Rule of 100? In general, the older an investor is, the more they tend to allocate to fixed income securities like bonds. Here’s the table from the suitability section of common stock:

| Age | Stock % | Bond % |

|---|---|---|

| 30 | 70% | 30% |

| 45 | 55% | 45% |

| 60 | 40% | 60% |

| 70 | 30% | 70% |

The Rule of 100 is often easiest to apply to bonds: an investor’s age roughly matches the percentage of bonds in their portfolio. This is a general guideline, not a rule that always fits. Some older investors are aggressive and can afford more volatility (for example, an 80-year-old billionaire might allocate heavily to common stock). Some younger investors are more risk-averse and prefer stability. Use the Rule of 100 as a generality, and remember there are exceptions.

Even though bonds are often viewed as “safe,” many bonds carry meaningful risk. Junk bonds and other higher-risk debt securities may offer higher yields, but investors can lose significant money if a default occurs.

Interest income is the primary benefit bonds provide. If an investor isn’t seeking income, another asset class may be more suitable. One exception is zero coupon bonds, which pay interest only at maturity. If an investor wants a predictable payout years in the future but doesn’t need income along the way, a long-term zero coupon bond could be suitable.