Long calls

This chapter covers the fundamentals of long call options contracts. To get comfortable with the language used when discussing options, watch this video:

When an investor goes long a call, they are bullish on the underlying security’s market price. Buying a call gives the holder the right (but not the obligation) to buy the stock at the strike price.

- If the stock’s market price rises above the call’s strike price, the holder can potentially profit by exercising the option (“call up” - the call is “in the money”).

- If the market price stays below the strike price, the holder won’t exercise and will realize a loss equal to the premium paid (the call is “out of the money”).

Let’s work through a few examples to understand long calls better.

Long 1 ABC Sep 75 call @ $6

This contract gives the right to buy ABC stock at $75 per share. The option costs $600 ($6 × 100 shares) and expires on the third Friday in September.

The investor is betting that ABC’s market price will rise above $75 before expiration. If it doesn’t, the option will expire worthless, and the investor will have paid $600 for a contract they never used.

Math-based options questions should be expected on the exam. They typically ask about potential gains, losses, and breakeven values. Let’s go through each.

A long call’s maximum gain is unlimited. The contract above allows the investor to buy 100 ABC shares at $75 any time before expiration. If the market price rises, the investor can exercise, buy at $75, and then sell at the higher market price. The higher the market price goes, the larger the potential gain.

For the following examples, assume the investor sells the shares immediately after exercising.

An investor goes long 1 ABC Sep 75 call @ $6. The market price rises to $100. What is the gain or loss?

Can you figure it out?

Answer = $1,900 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$600 |

| Exercise - buy shares | -$7,500 |

| Sell shares | +$10,000 |

| Total | +$1,900 |

At a $100 market price, the call is $25 in the money ($100 − $75). The investor exercises, buys 100 shares for $75 per share, and immediately sells them for $100 per share.

- Gain from exercising and selling shares: $25 × 100 = $2,500

- Subtract the premium paid: $2,500 − $600 = $1,900

The strike price is fixed at $75, but the market price can keep rising. That’s why the maximum gain is unlimited.

Even though the maximum gain is unlimited, a long call doesn’t automatically produce a profit just because the market price rises above the strike price. The increase has to be large enough to cover the premium.

Let’s try another example with the same option:

An investor goes long 1 ABC Sep 75 call @ $6. The market price rises to $81. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $0 (breakeven)

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$600 |

| Exercise - buy shares | -$7,500 |

| Sell shares | +$8,100 |

| Total | $0 |

At $81, the call is $6 in the money ($81 − $75). Exercising creates a $600 gain on the shares ($6 × 100), but the investor paid a $600 premium upfront. Those offset, so the investor breaks even.

When investing in calls, the breakeven can be found using this formula:

With a strike price of $75 and a premium of $6, the investor breaks even when ABC stock is at $81 per share. At this market value, there is no profit or loss.

If the market price of ABC doesn’t rise far enough above $75, the investor can still have a loss even though the option is in the money. For example:

An investor goes long 1 ABC Sep 75 call @ $6. The market price rises to $79. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $200 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$600 |

| Exercise - buy shares | -$7,500 |

| Sell shares | +$7,900 |

| Total | -$200 |

At $79, the call is $4 in the money ($79 − $75). Exercising creates a $400 gain on the shares ($4 × 100), but the $600 premium is larger, so the overall result is a $200 loss.

Expiration is the worst-case scenario for investors holding long options. When a long call expires out of the money, the investor loses the entire premium.

An investor goes long 1 ABC Sep 75 call @ $6. The market price falls to $73. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $600 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$600 |

| Total | -$600 |

At $73, the call is $2 out of the money ($73 − $75) and has no intrinsic value. When the market price is below $75, exercising doesn’t make sense: the investor would be paying $75 for stock that’s available in the market for $73. So the investor lets the contract expire and loses the premium.

Long options can only lose the amount spent on the premium. If exercising would result in a loss, the investor will let the option expire.

Investors can also perform closing transactions to close their options before expiration.

An investor goes long 1 ABC Sep 75 call @ $6. After ABC’s market price rises to $79, the premium rises to $9, and the investor performs a closing sale. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $300 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Buy call | -$600 |

| Close call | +$900 |

| Total | +$300 |

The market price increased, and the option premium increased as well. Unlike the strike price, the premium isn’t fixed - it fluctuates based on market conditions.

Here, the investor bought the call for $6 and later sold it for $9.

- Premium increase: $9 − $6 = $3 per share

- Options represent 100 shares: $3 × 100 = $300 gain

To find profit or loss on a closing transaction, compare the premium paid to the premium received.

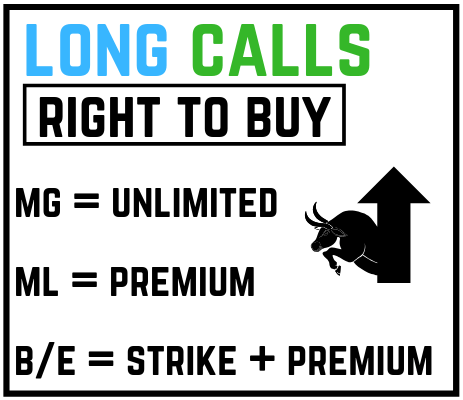

Here’s a visual summarizing the important aspects of long calls: