Now that you know the federal registration process for securities, the next step is understanding when issuers can avoid it. Registration is time- and cost-intensive, so many persons try to use an exemption when one is available.

The Securities Act of 1933 provides exemptions for certain issuers, issues, and transactions. When an exemption exists, it’s typically because the investing public faces limited risk.

There are two general types of exemptions:

Additionally, we’ll discuss Rule 144, which applies when investors purchase non-exempt securities through exempt transactions.

Exempt securities are always exempt from registration, regardless of the situation or type of transaction. A major advantage of raising capital with these investments is that issuers can avoid the lengthy process and costs associated with registration.

These are the exempt securities we’ll cover in this section:

Government securities

US Government and all municipal (state and local government) securities are exempt from registration. These are the most commonly cited government securities:

Insurance company products

Insurance companies are regulated under their own laws. Most insurance products are generally exempt, but there’s an important exception: insurance products with a variable component are not exempt.

You’ll learn more about variable annuities in the annuities chapter, but for now, remember that variable annuities are a primary example of a non-exempt insurance product.

Technically, most insurance products do not meet the definition of a security, which makes them excluded from registration.

Bank securities

Banks are also subject to their own laws, so their investment products generally avoid registration. Bank securities are typically exempt, but bank holding company securities are not.

Bank holding companies are organizations that own banks and may also own other types of companies. Bank of America is an example of a bank holding company; in addition to banking services, it owns other companies like Merrill Lynch. Because of this structure, Bank of America securities (including its common stock) are not exempt from registration.

By contrast, a security issued by a bank that is focused only on banking activities is exempt.

Non-profit securities

Securities issued by non-profits - including charities, religious organizations, and social advocacy groups - are exempt. For example, if the Red Cross wanted to issue a bond, it could do so without registering it with the SEC.

Commercial paper and banker’s acceptances

As you learned in the corporate debt chapter, commercial paper is a short-term, zero coupon debt instrument. It’s sold at a discount and matures at par.

The Securities Act of 1933 specifies that any security with a maturity of 270 days or less is exempt from registration. Because of this rule, commercial paper is virtually always issued with a maximum maturity of 270 days.

The same concept applies to banker’s acceptances, which are short-term financing vehicles used by importers and exporters.

Railroad ETCs

Equipment trust certificates (ETCs) issued specifically by railroad companies are exempt. Common carriers like railroads are already regulated under other laws for their financial activities, so the Securities Act of 1933 doesn’t cover them.

Even if the issuer and the security itself are not exempt, an exemption may apply based on how the security is sold. In this section, we’ll cover two ways a non-exempt security can be offered and still qualify for an exemption:

Regulation D

Regulation D offerings are also called private placements. They involve selling securities to a private audience rather than to the general public.

The Securities Act of 1933 is designed to protect the general investing public. When an offering is limited to a smaller, non-public group, the rules are relaxed. If an issuer sells securities under Regulation D, it can avoid registration.

Many growing companies use private placements early on and later move to an IPO. The reason is straightforward: private placements allow the issuer to raise capital without the time and expense of registration. In an issuer’s ideal scenario, it would raise all capital through private placements.

However, Regulation D offerings are largely limited to accredited (wealthy and/or sophisticated) investors and a small number of non-accredited investors. Since the pool of accredited investors is limited, issuers often use private placements until they need more capital than that group can realistically provide.

For example, Airbnb participated in multiple private placements starting in 2008. It later completed an IPO in late 2020 when it sought a large amount of capital ($3.5 billion) that it likely couldn’t raise solely from accredited investors. Many companies follow this cycle:

Regulation D allows unregistered, non-exempt securities to be sold to an unlimited number of accredited investors. As a result, millionaires, billionaires, and institutions make up the majority of private placement investors.

If an investor meets any of the following characteristics, they’re accredited:

Accredited investors

*For an institution to qualify as an accredited investor, it cannot be formed solely for the purpose of purchasing securities in a private placement.

Even if an investor isn’t accredited, they may still be able to participate. Regulation D allows up to 35 non-accredited investors in a private placement.

Non-accredited investors must sign documents acknowledging that they understand the risks involved, especially given the reduced information available. Because a private placement avoids registration, investors won’t receive a prospectus. Instead, they receive disclosures in an offering memorandum, which is similar to a prospectus but typically less detailed.

Rule 147

Rule 147 allows issuers to avoid federal registration when they offer securities intrastate (within one state only). Federal agencies like the SEC generally focus on offerings that cross state lines. If an issuer sells all of its securities only in Colorado (or any other single state), it can avoid SEC registration.

Rule 147 includes several requirements. The issuer must be operating “primarily” in one state, and its headquarters must be located in the state where the offering occurs. Under the “80% rule,” a company is considered primarily operating in one state if:

Investors must be residents of the state. They must also wait 6 months before selling any Rule 147 securities to a non-resident. However, they may sell immediately to another resident of the same state.

Although Rule 147 offerings don’t have SEC oversight, state registration typically applies. In particular, intrastate securities are usually subject to state registration by qualification (more on this later in the unit).

When investors purchase non-exempt securities through exempt transactions, they’re subject to Rule 144. This rule is especially important for restricted stock, which is stock that is not registered with the SEC.

Common stock is non-exempt and must be registered to trade freely in public markets. Unregistered stock lacks the disclosures that normally come with registration, which is why the SEC restricts how it can be resold.

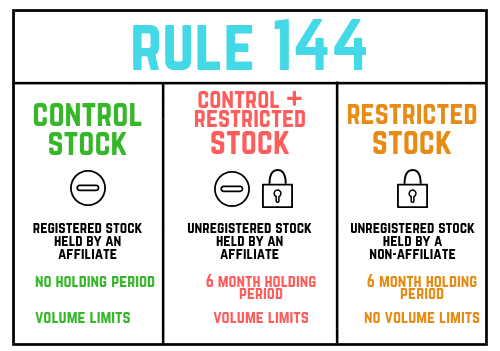

Restricted stock can be obtained in multiple ways, but it’s most commonly acquired through Regulation D private placements. Rule 144 requires restricted stock to be held for 6 months before it can be resold. After that holding period, the investor may sell the shares.

Rule 144 also regulates control stock, which is stock held by an affiliate. An affiliate is any officer, director, or 10% shareholder. In other words, if you’re an executive of the issuer or you own a large stake, you’re treated as an insider (affiliate). Rule 144 limits how quickly insiders can sell large amounts of stock.

This part of Rule 144 is often called the “dribble” rule. Insiders are frequently among the largest shareholders. If an insider were to sell a very large position all at once, it could put significant downward pressure on the stock price.

To reduce this risk, affiliates are subject to volume limitations. They may sell the greater of 1% of the outstanding shares or the four-week trading average, up to four times per year.

Sometimes an affiliate owns unregistered stock (for example, executives of privately held companies often own company stock). In that case:

When both conditions are true, both sets of Rule 144 requirements apply at the same time.

To summarize, here’s a visual representation of Rule 144:

One last item is Rule 144A, which is related to Rule 144. If restricted or control stock is sold to a Qualified Institutional Buyer (QIB), the requirements of Rule 144 do not apply.

A QIB is an institution with $100 million or more of investable assets. When a QIB is involved in the sale of restricted or control stock, the 6-month holding period and volume limitations do not apply.

Sign up for free to take 10 quiz questions on this topic