Short puts

This chapter covers the fundamentals of short put options contracts. To get comfortable with the language used when discussing options, watch this video:

When an investor goes short a put, they’re bullish on the underlying security’s market price. Selling a put creates an obligation: if the option is assigned (exercised), the writer must buy the stock at the strike price.

- If the stock’s market price falls below the put’s strike price (think “put down” - the put is in the money), the holder may exercise, and the writer must fulfill the purchase obligation.

- If the market price rises above the strike price (the put is out of the money), the holder won’t exercise, and the writer keeps the premium as profit.

Let’s work through a few examples to understand short puts better.

Short 1 ABC Sep 75 put @ $6

This contract obligates the writer to buy ABC stock at $75 per share if assigned. The writer received $600 for selling the option ($6 premium x 100 shares). The contract expires on the third Friday in September.

The investor is betting ABC stock’s market price stays at or above $75 through expiration. If ABC falls below $75, the holder may exercise the option, which can create losses for the writer.

Math-based options questions should be expected on the exam. They typically ask about potential gains, losses, and breakeven values. Let’s go through each.

An investor goes short 1 ABC Sep 75 put @ $6. The market price falls to $0. What is the gain or loss?

Can you figure it out?

Answer = $6,900 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell put | +$600 |

| Assigned - bought shares | -$7,500 |

| Share value | +$0 |

| Total | -$6,900 |

At $0, the option is $75 in the money. This is the worst-case scenario for a put writer. We can assume the investor is assigned, which requires buying 100 ABC shares at $75.

- The shares are worth $0, so the investor loses $75 per share.

- That’s a $7,500 loss from assignment ($75 x 100).

- The $600 premium received up front offsets part of that loss, leaving a net loss of $6,900.

The maximum loss for a short put can be found using this formula:

Here, the strike price of $75 minus the premium of $6 gives a maximum loss of $69 per share (or $6,900 overall).

In the short call chapter, we learned an option is “naked” when it’s sold without a hedge (protection). The same idea applies to a short put.

A short put is risky because assignment can force the investor to buy shares at the strike price when the market value is lower. In the worst case, the investor buys worthless shares at the strike price.

In the next chapter, you’ll learn how investors protect themselves from risk on short options. For now, here is a quick list of investments that would cover a short put:

- Short shares

- Long put

- Cash (equal to the maximum loss)

The risk of a short put comes from being forced to buy shares at the strike price and then potentially having to sell them at a lower market price (or not being able to sell them at all if they’re worthless).

-

If the investor is short the shares, the sale already occurred. When the put is assigned, the investor effectively buys back the shares at the strike price, closing the short position. The investor doesn’t have to worry about selling the shares later at a lower price because the sale happened when the stock was sold short.

-

If the investor owns a put (in addition to the short put), they keep the right to sell the shares purchased at assignment at the long put’s strike price. Even if the market price drops sharply, they can exercise the long put and sell at that higher strike price.

-

While cash doesn’t prevent losses, holding cash equal to the maximum loss of a short put technically “covers” the put. The investor has enough funds available to meet the obligation. Remember that cash cannot cover a short call because a short call’s risk is unlimited.

Let’s look at an example that’s more likely to occur.

An investor goes short 1 ABC Sep 75 put @ $6. The market price falls to $60. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $900 loss

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell put | +$600 |

| Assigned - bought shares | -$7,500 |

| Share value | +$6,000 |

| Total | -$900 |

The market price fell to $60, so the option is in the money by $15. After assignment, the writer must buy 100 ABC shares for $75.

- The shares are worth $60, creating a $15 per share loss.

- That’s a $1,500 loss from assignment ($15 x 100).

- Subtract the $600 premium received up front, and the net loss is $900.

Investors who sell puts don’t always lose money. Even if ABC’s market price falls below $75, the writer must lose more than the premium to end up with an overall loss.

Let’s work through another example.

An investor goes short 1 ABC Sep 75 put @ $6. The market price falls to $69. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $0 (breakeven)

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell put | +$600 |

| Assigned - bought shares | -$7,500 |

| Share value | +$6,900 |

| Total | $0 |

At $69, the option is $6 in the money. The investor is forced to buy ABC stock at $75 when the shares are worth $69.

- That’s a $6 per share loss, or $600 total ($6 x 100).

- The $600 premium received offsets the $600 assignment loss.

- The result is breakeven.

When investing in puts, the breakeven can be found using this formula:

You probably noticed this is the same breakeven formula used for long puts. The long and short positions are opposites, but they break even at the same underlying market price.

With a strike price of $75 and a premium of $6, the breakeven market price is $69 per share.

The breakeven formula is also the same as a short put’s maximum loss formula. The difference is how you use it:

- Maximum loss is a dollar loss, so you multiply by 100 to get the per-contract amount.

- Breakeven is a stock price level, so you don’t multiply by 100.

If ABC’s market price doesn’t fall too far below $75, the investor can still make a profit. For example:

An investor goes short 1 ABC Sep 75 put @ $6. The market price falls to $74. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $500 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell put | +$600 |

| Assigned - bought shares | -$7,500 |

| Share value | +$7,400 |

| Total | +$500 |

At $74, the option is $1 in the money. Assignment forces the investor to buy 100 ABC shares at $75 that are worth $74.

- The assignment loss is $1 per share, or $100 total.

- After including the $600 premium received, the net result is a $500 gain.

Expiration is the best-case scenario for investors writing (going short) options. If the option expires worthless, the investor keeps the premium and never has to fulfill the obligation. The same applies to short put contracts.

An investor goes short 1 ABC Sep 75 put @ $6. The market price rises to $84. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $600 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell put | +$600 |

| Total | +$600 |

At $84, the option is $9 out of the money and has no intrinsic value. When the market price is above $75, the holder won’t exercise. They wouldn’t choose to sell stock for $75 when it can be sold in the market for $84.

A quick way to think about assignment for puts is “put down.” Puts are exercised when the underlying market price is below the strike price. That isn’t true here, so the option expires.

Investors with short options can only make the premium - nothing more. If exercise occurs, losses start reducing the premium and can eventually create a net loss.

Writers can also perform closing transactions to exit their obligations before expiration.

An investor goes short 1 ABC Sep 75 put @ $6. After ABC’s market price rises to $79, the premium falls to $2, and the investor does a closing purchase. What is the gain or loss?

Answer = $400 gain

| Action | Result |

|---|---|

| Sell put | +$600 |

| Close put | -$200 |

| Total | +$400 |

To find the profit or loss on a closing transaction, compare:

- the premium received when the option was sold, and

- the premium paid to buy it back.

Here, the investor received $6 and later paid $2 to close. That’s a $4 net gain per share.

Since option premiums are based on 100 shares, the overall gain is $400.

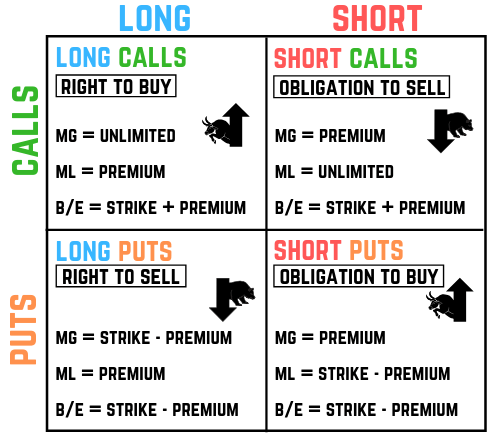

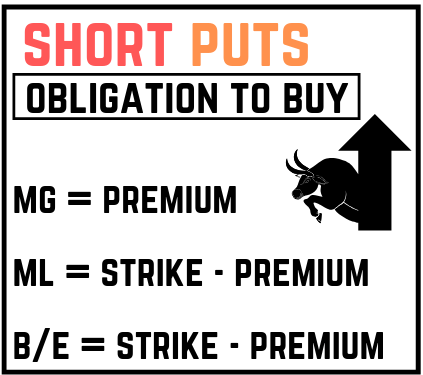

Here’s a visual summarizing the important aspects of short puts:

You’ve now been through all four versions of options: long calls, short calls, long puts, and short puts. The following visual puts it all together: